I often, perhaps too often, see the world through the lens of injustice. It’s a bend of mind I’ve had since childhood; I was one of those kids that said “but that’s not fair!” and constantly asked “why?”1 to the point of annoyance for my parents. It’s one of the reasons I went through law school, it’s the main driver of why I am pursuing the career I’m madly fighting for, and in part it’s a force behind this Substack. Looking through “best/most read books of 2024” lists reaffirms why I wanted to put this little Substack out into the world. And I gained something unexpected delightful from it in the creation of it, it’s been just over six weeks, but it kindled the desire to write and the hope that I might one day be a real writer.

Knowledge and empathy, both of which can be found through good literature, are two keys to combat injustice. A sort of literary version of Daryl Davis, who through friendship, has convinced over 200 KKK members to give up their robes2; that is, to share time with others is to make them familiar and known, to understand the commonalities between you and others whose identity (race, religion, country of origin, gender/sexuality) are unlike yours. Those are nice thoughts, but they also make reading sound like prescription. We read literature for pleasure, or most of us do anyway. Reading about others gives me that feeling that reading did when I was child: it transported me to far-off places and through it, I met interesting new people, it allowed me to travel without leaving my bedroom. It’s wonderful to read about people (somewhat) like me, but it’s equally wonderful to read about people who, on the surface aren’t like, to see and feel how the shapes of our hopes and dreams are more similar than dissimilar, to learn how different experiences mold our worldview, to explore the richness and complexities of the human experience, and through that, expand my own.

I had no intent of publishing a “best books of 2024” until several popped up in my feed. And I didn’t intend this, but I noticed that those lists were…well, so many of them only had white, Western authors. Yes, the publishing industry is biased toward publishing those authors, but it’s also biased that way because that’s what sell. It’s systemic. That reaffirms it feels important to put this little project into the world, though my life-long tendency has been to work very hard until I see signs of success, then to run away or drop as quickly as I can. If I ever reach some sort of “success” with this project, it’ll be important for me to continue at it for the reason that I started it: I was looking for literature about the sapphic (lesbian, women-loving-women…) experience, written by folks with that experience, and every list I’d come across had the smallest handful of books. I expanded that into “translated” literature because sapphic literature skews away from non-Western, non-white authors. The Substack’s become a catalog of books I’ve read, but not all books. I’m disinclined to review some of them, eg., I loved Jane Ellen Harrison’s Reminiscences of a Student Life (1925, republished 2024), and this week I loved Agustín Fernández Mallo’s The Book of All Loves. I’m not sure how to make either “social-political”, and chose not to review them and a few other. The best-of’s though, I re-read a few of them so I could review them.

My best-of has its biases. It tilts white-European; interestingly there are no American authors/books on it, although I’m American. It has a few Asian authors. The books on the list are from different eras; the early modernists (Bulgakov, Woolf), to the starkly modern (Erpenbeck, Ernaux, Debré), and the writers are of differing class (Ernaux v Debré as an example). Right now, I’m reading Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s The Most Secret Memory of Men (2021, trans 2023), and it’s excellent and there’s a high chance it’ll end up on my best 2025 list (though, no where near the end, so we’ll see). The best-of list appears first, the “worst of” list follows.

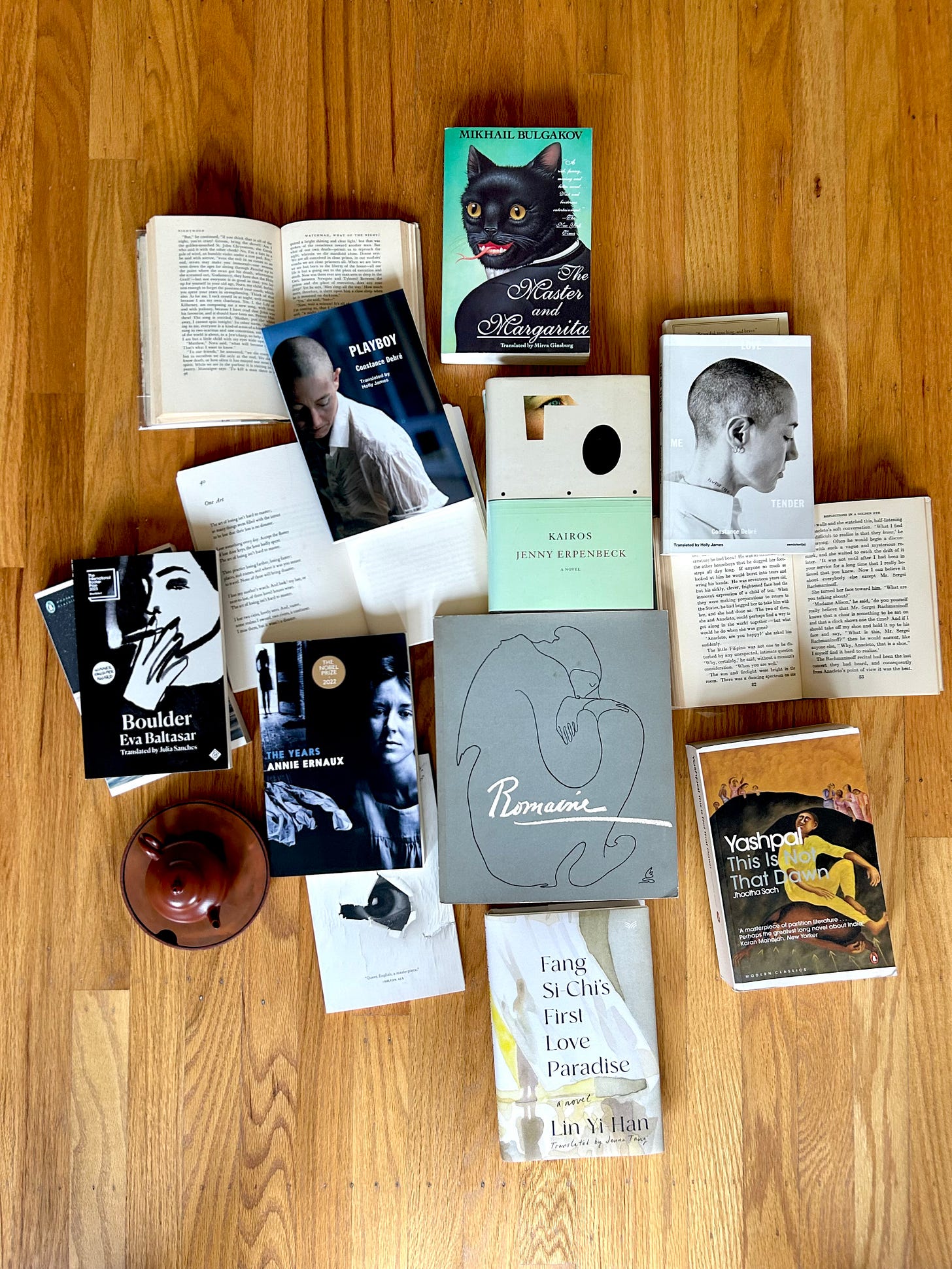

Here’s the best-of list:

Lin Yi-Han’s Fang Si Chi’s First Love Paradise. Devastating, heart-breaking, beautiful, drawing upon Chinese literature and written from that tradition - so poetic, full of metaphor. An emotional fever-pitch of a novel that’s unlike anything else. It’ll be the only novel she’ll ever write, if there’s any book you read in 2025, I hope it’s this one (review linked)

Constance Debré Love Me Tender and Playboy, for her deadpan, anxiety-laden, defiant, rebellious voice, for showing the reader that no matter what choices you make in how to live to your life, there are downsides and consequences, because many reviewers reduce her work and experiences to “came out as a lesbian and f-cked a lot of girls” but that’s not the crux of her work. It’s about class, financial anxiety, the legal system, misogyny and homophobia, motherhood, and the consequences (reviews linked)

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. Allegory, satire, slapstick comedy, speaks to love, and the corrupting influence of power, yet, always beautiful and poetic. There’s nothing like it, no wonder many people call it their favorite book (review linked).

Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos. Loved it so much I read it twice in one year. For its prose and the elegance of the metaphor she creates. It’s much more emotional and raw if compared to her previous works, but it is Erpenbeck, so the overall tone is still cool and detached (review linked).

Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. Read it twice this year alone also. Instead of taking a serious approach to gender inequality, sapphic love, and British xenophobia, Woolf uses satire, playful humor, and stunning prose to delicately make her opinion known. So delicately that this book was not censored nor banned (review linked).

Eva Baltasar’s Boulder. The prose, the prose! It’s unsurprising that Baltasar was a poet before she wrote three novellas. I wrote that it was “[s]tark, full of metaphors, poetically blunt, powerful, straightforward, somehow brittle”. Yes, it’s lesbian, but it’s about failures in communication leading to devastation, and about the desire to live life on one’s terms, and to live with the consequences (reviewed linked).

Annie Ernaux’s The Years. Ernaux extends the personal and internal to speak for her generation, makes it universal, her “I” becomes “we” and back again. She speaks to you directly, conversationally, but you’re having the most interesting conversation with someone brilliant, independent, and aware of everyone and everything. She writes of the limitations of growing up working class, which isn’t the class of person publishers usually publish. Nobel-prize winning autofiction, deservedly so (review liked).

Yashpal’s Jhoota Sach. Considered by many (including yours truly) to be the best book on the partition of India into India and Pakistan. Deeply philosophical and informed by his time as a freedom fighter rather than just the theoretical and researched. Complex characters, sensitively written, a delicate showing of the life-altering, life-taking devastation of a decision carelessly and quickly made. I might have read it repeatedly…if it wasn’t 1100 pages of fine print (review linked)

The worst reads:

John Williams’ Stoner (reviewed linked). With both Stoner and The Safekeep, part of my dislike comes from the general love for the book. I have nothing against The Safekeep, it’s not my favorite category of literature, rather the reactions and reviews of it upset. After the first seventy or so pages, Stoner became an unpleasant read, with Williams writing to bluntly tell and sell his reader on his personal philosophies. Williams thought his main character a hero, yet, he rapes his wife repeatedly, devastates his parents and disregards their lifetime of work and their attempt to better his life, uses his friends, and…regards himself as a victim of the oppressed, while the book argues that “undesirables” are invading academia, harming white men such as Stoner. I left the book in a Little Free Library. I’m sure someone will love it since it’s so popular, but that person wasn’t me.

Dinah Brook’s Lord Jim at Home. I’ve seen reviews argue that people want to read about abuse in a gawping, voyeuristic way. The popularity of A Little Life confirms that, I suppose…but I don’t. I’ll read about abuse if there’s a purpose, if it opens one’s eyes to the realities of abuse. But detail upon detail of the horror of it? No thank you.

Christine Argot’s Incest. The extremely-heightened anxiety and frequent negative remarks on the grossness of female genitalia were too much for me. I don’t think it’s a bad book, just…I couldn’t finish it. Didn’t even make it to the incest, thankfully.

Giorgio Bassani’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis. I took a class on Jewish literature in college. Fell in love with Kafka through it. This book is about the Jewish experience, and about the holocaust…and if you liked being hammered in the head with a sledgehammer wrapped in the roses, maybe you’ll appreciate it more than I did. Maybe I need to give it another chance, but I’ve tried twice. I picked it up because a New York Times writer called it her favorite book. It’s not mine, I tried, and tried, and couldn’t. Plenty of excellent holocaust literature and memoir out that I prefer to this.

Today, January 4, 2025, would have been my paternal grandmother’s 99th birthday. She answered my why’s, and was my favorite person.

Brown, Duane. How One Man Convinced 200 Ku Klux Klan Members to Give Up Their Robes. NPR. August 20, 2017. https://www.npr.org/2017/08/20/544861933/how-one-man-convinced-200-ku-klux-klan-members-to-give-up-their-robes Accessed January 4, 2024.