The Rape Novel: A Personal Story

The reality of rape through Lin Yi-Han's Fang Si Chi's First Love Paradise

To start, I want to grab you by your figurative shoulders and say, please read this book. Because, a while ago, I’d read that Western publishers receive a lot of novels and memoirs from survivors of assault about assault, and those publishers all but ignore them, considering them unpublishable and uninteresting. A handful, notably, Chanel Miller’s Know My Name make it through, but they’re often based on the person (or their story’s) fame, and so, aren’t wholly the story of rape but instead about fascination, curiosity, and often, about credibility.

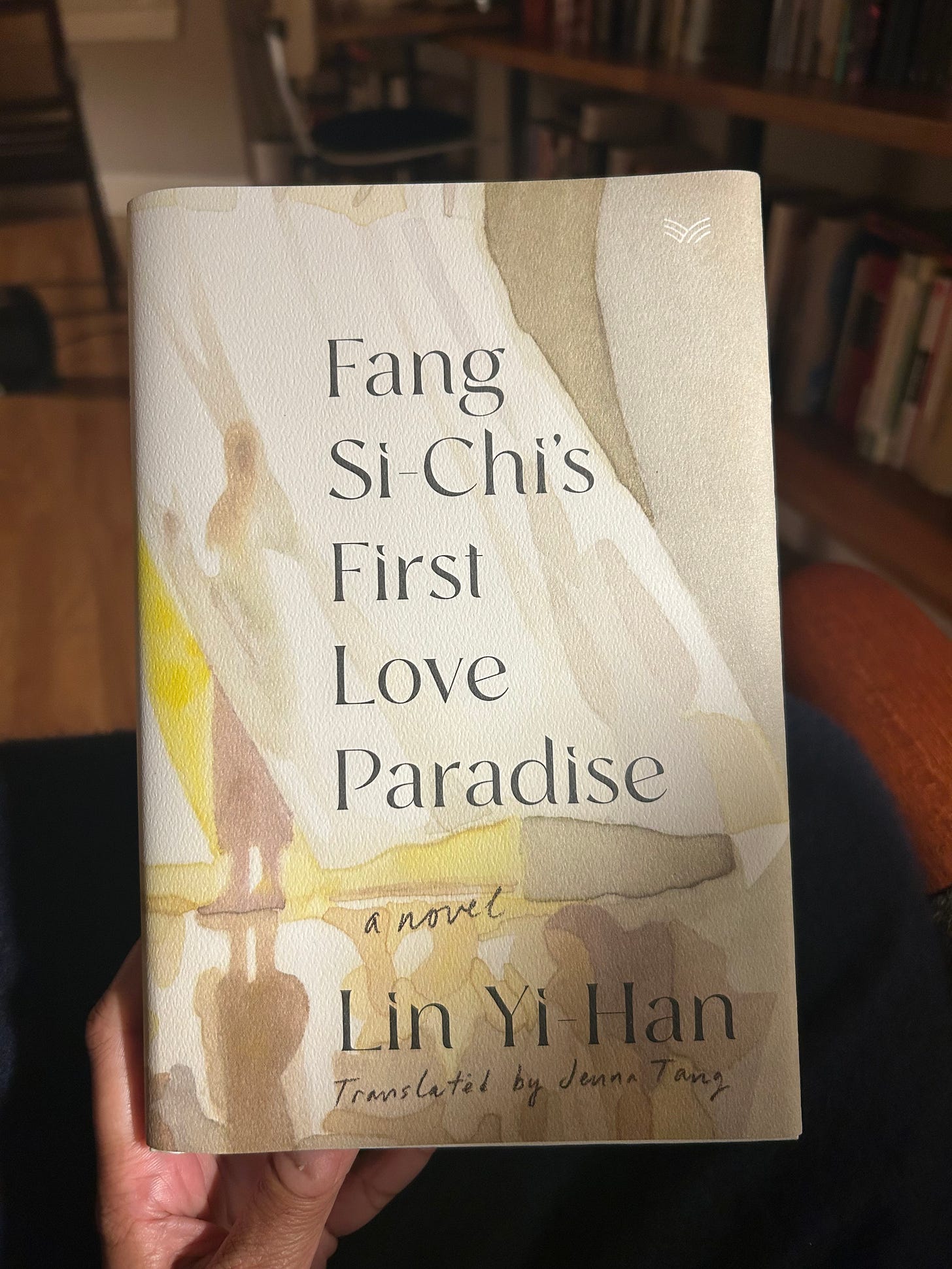

Going against that trend is this book, Lin Yi Han’s Fang Si Chi’s First Love Paradise (2017, trans 2024). Harper-Collins calls it “one of the biggest books to come out of Taiwan in the last decade”, and it focuses on the repeated rape of a legal and literal child. It’s the first and only novel by Lin. “Only” is telling, because like another young female Taiwanese author, Qiu Miaojin, Lin also took her life at the age of twenty-six. That lin…