If you look through the literary canon - the literary stuff, not fantasy or romance or YA - there are few women of color lesbian writers, and very few outside of the West. Qiu Miaojin would be respected for being the most famous of non-Western, non-white lesbian writers, but she’s the most well-known because she’s also brilliant. Her writing is “postmodern pastiche of diaries, vignettes, mash notes, aphorisms, exegesis, and satire by an incisive prose stylist and major countercultural figure” according the NYRB blurb. An example of her inventiveness: many chapters begin with an allegorical story about a crocodile, as Miaojin equates being a crocodile amongst humans with the experience of being a lesbian in heteronormative Taiwanese society through short allegorical stories at the beginning of several chapters of Notes on a Crocodile. In one, the crocodile finds a flyer which leads her to a secret ball with other crocodiles, where she wonders if she’s adapted to human society as well as the other crocodiles. This was late 1980s Taiwan. Homosexuality was starting to be discussed, albeit as a curiosity (as a crocodile among humans would be), transgressive, something illicit and exciting but also not wholesome. Finding queer spaces and community in Asia would be difficult, and it’s still not easy today (if queer women complaining about this on social media are to be believed). Nor it is particularly easy in the US, even in the city with the highest concentration of lesbians in the U.S. Nor should the West applaud itself for achieving equality for queer folks (because it hasn’t, and equality is becoming less likely in the U.S (see last paragraph)).

For English-speaking audiences, the fact that so many of Qiu’s works are now available in translation acknowledges her importance for contemporary queer and Sinophone cultures, as well as her vital addition of yet another counterpoint to falsely universal LGBTQ “liberation” stories that recognize only white, Western (especially male and Anglophone) understandings of “transgressive sexualities.”

Henrich, Ari Larissa. “Consider the Crocodile: Qiu Miaojin’s Lesbian Beastiary.” The Los Angeles Review of Books. May 17, 2017. Accessed Sunday, December 8, 2024. [linked]

Qiu Miaojin was an underground queer icon in Taiwan, so iconic that the name of the main character in Notes on a Crocodile (1994) is Taiwanese slang for lesbian. There’s no Western counterpoint for her, no lesbian writer quite as iconic. Her work gained a larger readership in Taiwan, won awards, and seemingly she was headed for a brilliant literary career had she not ended her life at the age of twenty-six, a fact that’s always included in every biography, however brief, about her.

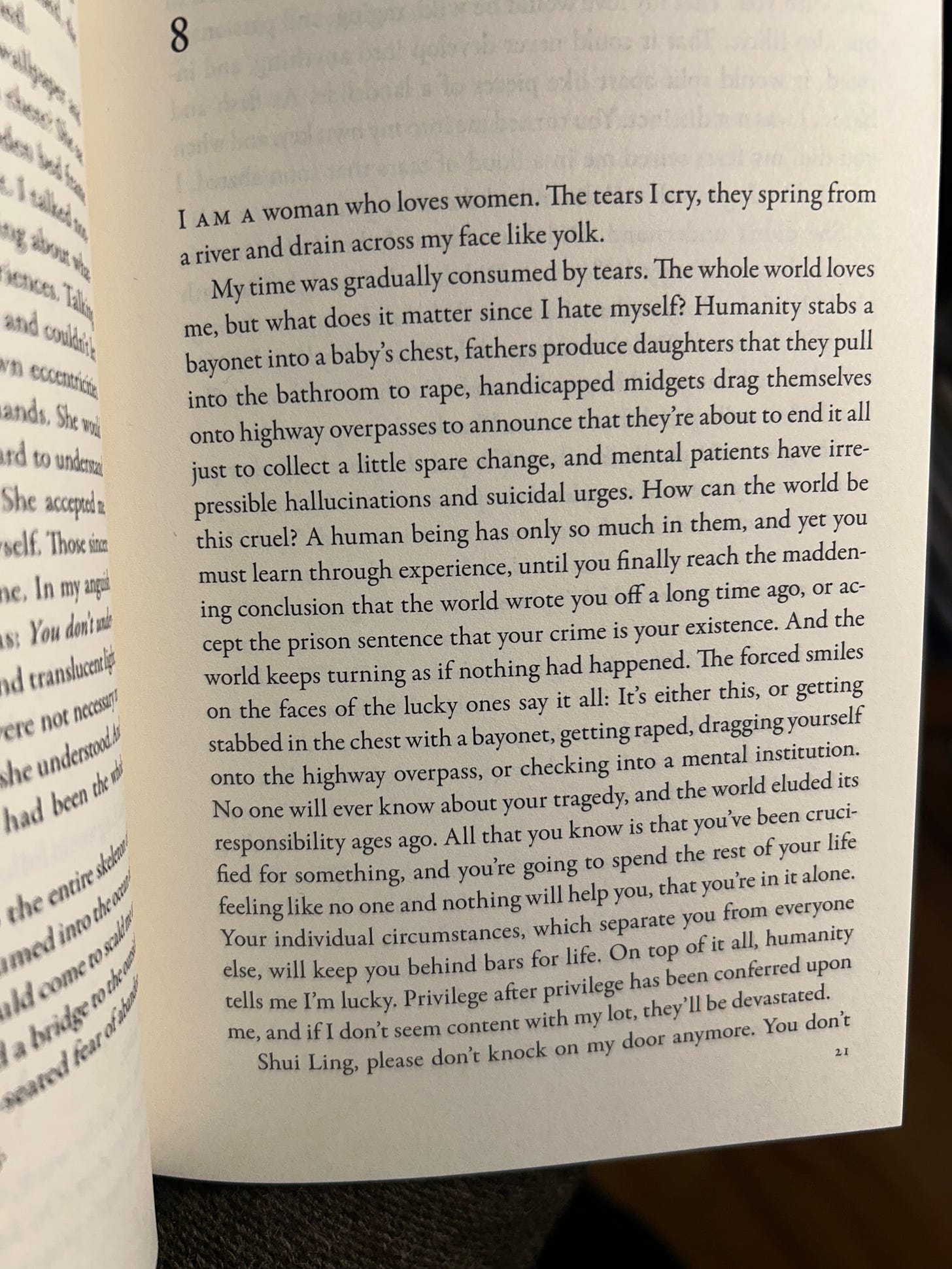

If you read her work, the suicide isn’t surprising. “I am a woman who loves woman. The tears I cry, they spring from a river and drain across my face like yolk”. It’s a defining moment in Taiwanese queer culture, or so Ari Larissa Henrich writes in the above-cited review for LARB. The lines alone was inspiring enough that I took a photo of it while I was reading it, before I read Henrich’s review. I also took the photo because what comes after the lines made me want to scream. Here’s the rest of what’s on that page:

This passage captures something of the tone of the book, and that tone feels more heightened her suicide-letter-of-sorts, Last Words from Montmartre (1994). I remember an Instagram post calling this book - the book this passage is included in - “cozy” and “autumn vibes”. Her writing strikes me as the opposite: it’s some of the darkest I’ve read, raw, powerful, and heavy with anxiety. She’s an author that captures depression unlike any other I’ve read, truly captures the way it colors and changes your thoughts. Her narrator’s thoughts are the cyclical, repetitive rumination of a depressed person, the self-absorption, the youthful angst, the very youthful depressive presumption that whatever you think and feel in the moment is eternal, and the pain of being queer in a society that doesn’t accept homosexuality, of being told you’re lucky because you have other privileges.

Henrich writes

Notes also conveys an irrepressible excitement about the possibilities of gender and sexuality at a time when mainstream characterizations of those possibilities had not yet hardened into the current obsession with marriage equality as the benchmark of LGBTQ liberation (this is not nostalgia on my part, but rather anxiety about the enshrinement of heteronormativity — represented so often by the marriage equality movement — as a standard for rights that is founded as much upon who it excludes from “equality” as on equality itself, as if all anyone needs for happiness under the surveillance state is government recognition of one’s romantic life)…Qiu’s work may be dark, but now more than ever, it offers a provocative counterpoint to the blinkered optimism of gay rights as tethered to the interests of the state.

The narrator, Lazi, is attending one of Taiwan’s best universities, and lives in a major city. Here, she mets other queer folks, dates what the book blurb calls an “older” woman (less than two years older, this women is 20 to Lazi’s 18 years and 5 months). Yet, when I read Lazi’s narration, it seems menacing, gay male love described more violently than loving, lesbian love sometimes close, more often, Lazi’s experiences are a push-pull of unequal emotion between her and her love interest, complete with behavior that borders or is obsessive and doesn’t care for the consent or willingness. There is a sort of overwrought, nearly painful excitement that Lazi describes when she encounters a queer female couple that become friends, and some queer men, she talks of a fantasical post-gender world and what might that be…perhaps that’s supposed to be “irrepressible excitement”. It’s the sort of excitement you get when you chance upon something magnetic, in equal parts terrible and wonderful, you don’t trust it, you’re skeptical but too fascinated to pull away. It’s dark, and it feels dangerous.

And as an aside, marriage equality is not “government recognition of one’s romantic life”, it’s access to the legal rights granted through marriage - of wills and trusts, of power of attorney, of medical decisions, of parenting, of the immigration process (eg, because my older lesbian friend couldn’t marry her girlfriend at the time, her girlfriend enrolled in an expensive MBA program so that they could be together, and they’re now married and the mothers of twin sons)…of all sorts of things that most people don’t care too much, mostly because a lot of them apply when you’re much older and that straight people take for granted. Much of queer joyfulness comes from within, and from the community/found family that queerness grants - the latter is something Miaojin makes explicit in Notes… which is built on a foundational understanding of shared experience and shared sense of outsider status. This gross misunderstanding of marriage as a legal institution and strange take on queerness coloring a book review (so now I’ve also been colored by it) makes me feels a bit better for my takeaway of this book being quite different. Notes on a Crocodile is an excellent read, but I might stay away if I was in the middle of a depressive episode. When I read it, it felt as if a dark hand reached out to me from its pages, inviting me to sink into the despair the author must have felt as she wrote those pages.

Another CNY 2025 must-have 🫠

“I am a woman who loves woman. The tears I cry, they spring from a river and drain across my face like yolk” that hit right in the gut