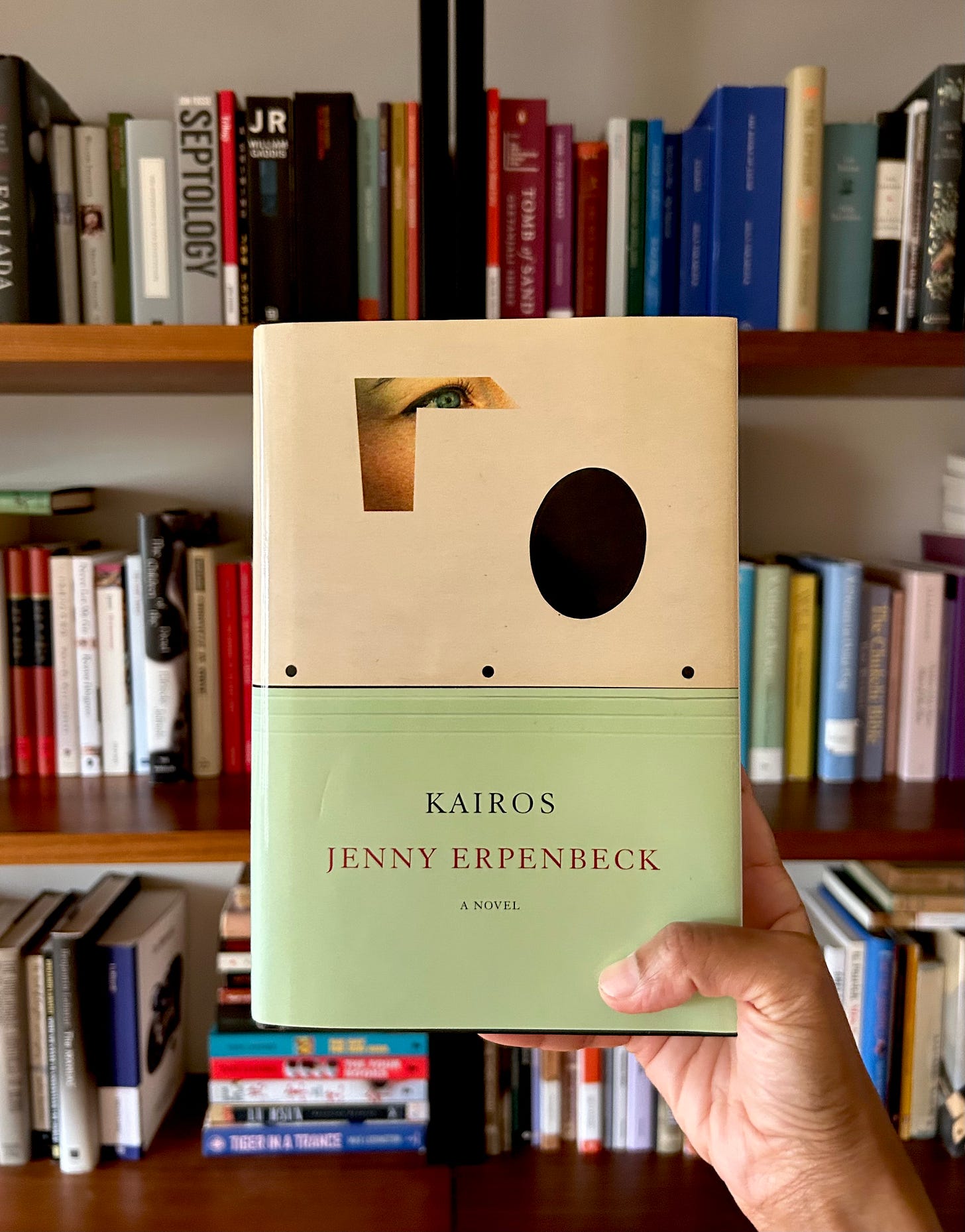

I read Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos (2021, trans. 2023 Michael Hoffman) at the end of last year, and again at the end of this year. Fitting for a novel named after a god of time. With the first read, I noticed Erpenbeck’s sophistication around writing about the complicated mechanisms of highly complicated, at times abusive, relationship. On my second read, I noticed more of Erpenbeck’s analogy of the relationship resembling end of days for East Germany (GDR, we’d say here in the U.S., but DDR much of the rest of the world would call it). Both times, I fell into the nostalgic, beautifully sorrowful spell Erpenbeck casts…

A man asks a woman if she will come to his funeral. She ignores the request until he asks again, and again, before she acquiesces. After his death, she goes through boxes of detritus accumulated during their relationship. Katharina is nineteen, and one day she leaves her house, walks into a bookstore, barely makes it onto a train. On that train, she glances, three times, at…