The Importance of Literature by Queer Women for A Queer Woman

aka, a short biography through the works of Constance Debré

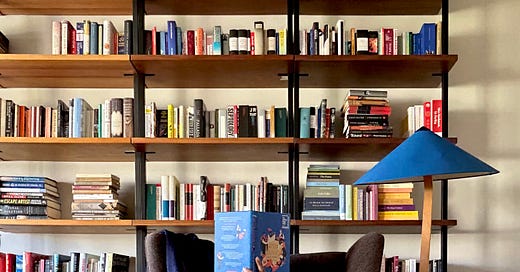

This summer, a woman asked me on a date to my favorite bookstore. I obliged. While wandering around that bookstore, she gave me a funny look after I excitedly pointed out the fourth or fifth explicitly queer book. I made an offhand joke, and my very queer taste in literature and art became a running joke during our brief courtship. I hadn’t realized how queer my tastes ran prior, and then I ran with it. This Substack was born.

I’ve put hours upon hours into finding queer lady literature, and one of my hopes for this Substack is that others use my site as a resource. On a more self-focused note, there’s the connectedness and sense of community I get through reading these books, all of which are written by women older than myself, as if I’m guided and mentored by them…and all of which I can relate to some aspect of myself. In reading their words, I find a different type of depth. In my one-sided conversation with a book, I’m free. The book itself takes me on a journey through the author’…