What the Pronatalists Get Wrong

The modern pronatalist movement, its motives, and a radical idea on supporting people who want to have children today

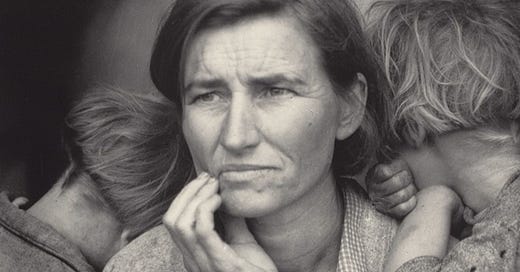

Dorothea Lange: Migrant Mother, 1936

The Cross of Honor of the German Mother was a “state decoration” awarded by the Nazi German government for mothers of four or more children. A bronze award went to German mothers of four to five children, a silver to six or seven children, and a gold metal to mothers of eight or more. Given what we know about Nazi Germany, it is no surprise that the award was extended to “ethnic German” women of Austria and nearby areas, but native-born women of Jewish or partial Jewish ancestry were not eligible.

The echoes of that Nazi eugenics program can be observed in today’s conservative push for women to return to the home, childbirth and childrearing.

The U.S Pro-Natalist Movement, and Its Deterrents

The United States’ White House of 2025 has recently proposed a few awards and ideas to incentivize people to have children. The idea include:

A one-time $5,000 award to every American mother following delivery

Reserving 30% of all Fulbright Scholarships (prestigious, government-backed international fellowship) for applicants who are married or have children

Government funded programs to educate women about their menstrual cycles

Tax credits to married couples with children, in which families receive more money back from the government for each additional child they have

Lowering the cost of IVF procedures

The U.S. Vice President recently said something to effect of wanting to have “beautiful men and women” to have children. There’s a lot of alarm around two modern American pronatalists, Malcolm and Simone Collins, and their influence on the White House. Their ideas include:

Using IVF and scanning embryos to select for traits like higher IQ

Pushing “elites” to have more children to avoid economic and societal collapse1

Taken together, this also sounds in line with Nazi Germany — it’s not merely that the conservative American pronatalists want American women2 to produce children, it also sounds as if a specific subset of people are being encouraged to produce “superior” children. Add to this the Heritage Foundation, the conservative think tank with (supposedly) outsized influence on the American government, which advocates for Americans to:

Use natural methods such as family planning over IVF

Promoting birth for “families” — nuclear families of a (male) husband and (female) wife

On the liberal/left, there’s a tendency to compare the current U.S. regime to the beginnings of Nazi Germany. Which is in part why I did so at the beginning of this article — that, and anything that sounds like forced sexual intercourse and forced birth alarms me, since (1) I’m a woman, (2) I’m in particular involved in the movement to end rape/sexual violence, and (3) I don’t fit into the neat and tidy hyper-gendered role of childbirth, childrearing, and managing a household and family.

Because I tend to read more pro-feminist news and sources, I can tell you that the left/liberal/progressives argue that the reason that women aren’t having children is that they cannot afford to have children, and that it is dangerous to for women to have children. The arguments, including some of my own:

Among developed nations, the U.S. has the highest maternal and infant mortality rates. Black women are disproportionality affected by this. The rate of sepsis has shot up by 50% in states like Texas, following the Dobbs decision against abortion rights.

The cost of raising a child. A $5,000 care credit is nice, but the average cost of raising a child (pre-college) is about $300,000 in the U.S. Rising costs include cost of housing, food, and day care.

Add to that the lack of job security and the precarious shift from full time employment to contract and gig work — with fewer legally mandated employee protections, employee benefits (such as health care coverage through the employer), lack of eligibility for unemployment benefits, and a lack of stability in hours and pay.

Issues of intersectional feminism and social justice. If the right to marry (same sex) feels precarious, queer people are less likely to want to have children. As a person of color and especially as a Black person, you’re less likely to want to bring your child up in a world where that child will face systemic discrimination and inequality.

This signals that the so-called American Dream is gravely ill. Migrating classes, eg., going from working class to middle class, is more difficult in the U.S. than it is in other developed nations, such as Canada and France - data shows us that a smaller percentage can do this in the U.S. This is in part because Americans have fewer social/governmental support mechanisms, such as health care and college education.

In this essay, I used the American conservative pronatalist movement as the start point intentionally — as the U.S. is particularly lacking in governmental and social (communal, familial) support systems.

The lack of social support and safety nets (both social and financial). The ways in which community and family support have changed over the last few generations.

The role of women. To write Holding It Together: How Women Became America's Safety Net, Jessica Calarco spent 4,000 hours interviewing 400 women about the unequal burden placed on them. Some examples from the book:

An aunt is pushed into caring for her niece and nephew at age fifteen once their family is shattered by the opioid epidemic

A daughter becomes the backstop caregiver for her mother, her husband, and her child because of the perceived flexibility of her job

Widowed single mother struggles to patch together meager public benefits while working three jobs

Five years ago, after Kristen’s mom unexpectedly passed away, quickly after her dad passed away, she found myself in a position where she decided to take on the care of her 47-year-old brother with Down syndrome (source)

A woman who quit her job to care for her disable son — the woman quit as she made less than her husband. In the years following, elder parent care fell to her as well.

Consider this: a woman makes less money than her husband (since women generally do), and they have a child. The husband is abusive. The woman feels cannot leave as she cannot afford to support the child on a single income.

The latter two main points that this essay that we, as individuals in community, can change.

The Motives of the Pronatalist Movement

In No Futures, Lee Edelman gets into why the pronatalists push people into childbirth and childbearing. In short, it has nothing to do with the warm and fuzzy reasons that people want to have children, nor with the practical and care-based things that children need to survive and thrive. It has everything to do with ordering society, and with pushing people into specific political beliefs in the name of “protecting the children”.

This mythical child is the very sort that the pronatalist has in mind when they argue in favor of increasing childbirth — as the Collins, a white, well-off couple who describes themselves as elite — unashamedly make clear in their brand of pronatalism. The child’s education, access to health care, food, clothing, shelter, emotional and physical well-being…are all are secondary to the abstract need to protect them. In Nazi Germany, it was Jewish and Romani people. In the Reagan and Thatcher eras, it was against gays and lesbians. Today, it’s against immigrants and trans people. Whichever abstract group is made the enemy, the mythical child is a perfect rationale for attack.

Families must continue to be the foundation of our nation. Families—not government programs—are the best way to make sure our children are properly nurtured, our elderly are cared for, our cultural and spiritual heritages are perpetuated, our laws are observed and our values are preserved. … [I]t is imperative that our government’s programs, actions, officials, and social welfare institutions must never be allowed to jeopardize the family. We fear the government may be powerful enough to destroy our families; we know that it is not powerful enough to replace them.

Edelman’s book is titled No Future because the future never arrives. Each generation is doing everything they are doing for a mythical future — since that’s the case, they are less concerned about the here-and-now, improving society for the people living in it. Instead, the concern for improvement is always shifted to the next generation. It’s no surprise that this dovetails with religion — with the idea that everything we do in the here-and-now is to prepare for the afterlife.

…like the parents of mankind’s children, succumbs so completely to the narcissism—all-pervasive, self-congratulatory, and strategically misrecognized—that animates pronatalism, why should we be the least bit surprised when her narrator, facing his futureless future, laments, with what we must call a straight face, that ‘‘sex totally divorced from procreation has become almost meaninglessly acrobatic’’? Which is, of course, to say no more than that sexual practice will continue to allegorize the vicissitudes of meaning so long as the specifically heterosexual alibi of reproductive necessity obscures the drive beyond meaning driving the machinery of sexual meaningfulness so long, that is, as the biological fact of heterosexual procreation bestows the imprimatur of meaning-production on heterogenital relations.3

Edelman’s prose is admittedly dense, and rooted in French theorists (eg, Jacques Lacan). To translate into plainer English: the mythical child gives meaning to the narcissistic, “self congratulatory” pronatalist society. Producing these mythical children provides a sort of “machinery of sexual meaningfulness” — getting into the idea of heterosexual sexual intercourse sanctioned through marriage, as a means of production for the state.

Edelman’s work is also a classic of queer theory. He offers up the idea that people who do not fit neatly into this machinery of child-production are queer. Thus, his theory advocates for feminism: for it is women who do not produce children, including and perhaps especially, women who opt for abortion, are the most “queered”, the most othered, under the pronatalist regime.

And thus, by queering/othering women in particular, the pronatalists can also achieve another conservative goal: to limit the participation of women in the public sphere. Because if women are primarily focused on child-rearing (versus child-rearing being shared amongst parents and society), then women are at home with the child.

As an alternative for women who want children and to participate in the public sphere, we can look at additional support for women, children, and the nuclear unit.

Rethinking the Nuclear Family

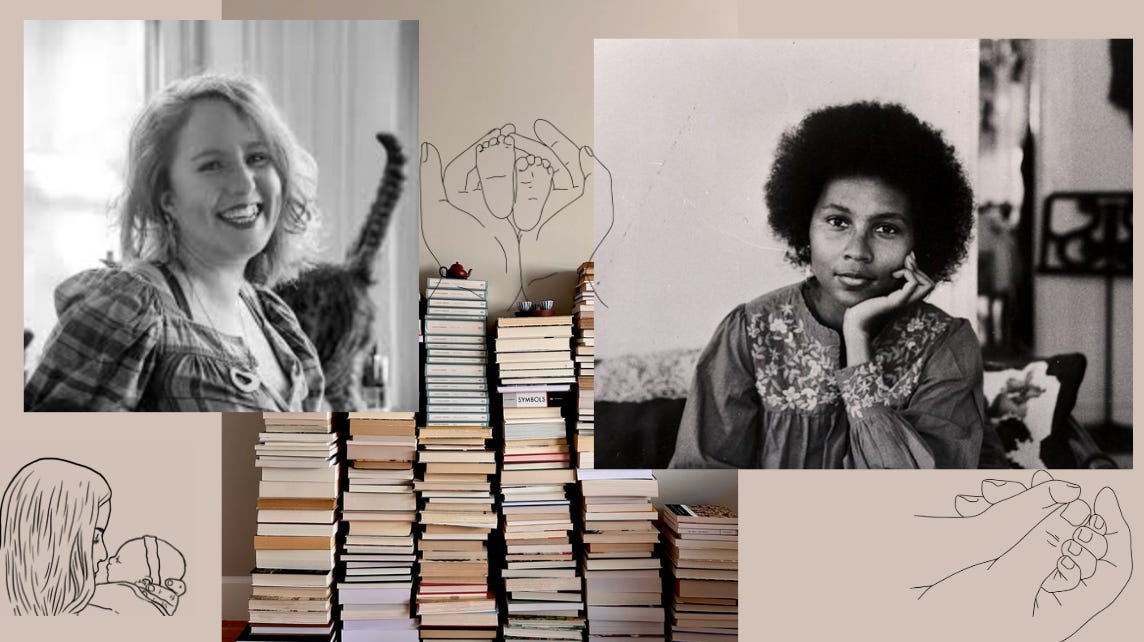

Sophie Lewis (blonde, top-right), bell hooks (dark curly hair, top-left), image of books behind them, three graphics: feminine figure kissing baby, hands holding baby feet, adult hand holding baby hand

“We will protect, defend, and promote the American Family at all costs. The nuclear family is crucial to civilization, it is God’s design for humanity, and it must be protected and celebrated. To say otherwise is to deny science.”

Republican senator Rick Scott | source

You might recognize the language I chose earlier, “means of production”. The slightly Marxist framing was intentional. That’s because I wanted to allude to the idea of the nuclear, child-producing family as being one that is the primary mechanism for teaching children ideas of discipline and obedience — in other words, creating obedient means of productions for the state. It is no surprise, then, that the household is also the primary source of abuse for children4.

“When you love someone, it simply makes no sense to endorse a social technology that isolates them; privatizes their lifeworld, arbitrarily assigns their dwelling-place, class, and very identity in law; and drastically circumscribes their sphere of intimate, interdependent ties.”

Sophie Lewis | source

In her Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against the Family, Sophie Lewis argues for a communal approach to reproductive labor. Lewis gets into surrogacy and gestational work5, but it’s the child-rearing aspects that are of more relevance here. The theory she’s arguing for is sometimes called family abolition, relating to the idea of ending the supremacy of the nuclear family.

I think for most people, especially people in the West, that sounds rather more alarming. What she’s arguing for a more communal, less nuclear approach to family and child-rearing. I’d argue not for the destruction of the nuclear family, but for a broader definition of family and community. A different definition that includes greater support for the parent(s) and children, and a restructuring based on care for one another.

The idea isn’t brand-new. It was also popular among some second-wave feminists and in early queer theory. It’s also why intersectionality in theory is so important: in many cultures in the Global majority (global south), children are raised communally, with extended family and close friends playing a larger role in child-rearing. It’s the idea that “we all deserve more mothers”, and “mothers” deserve more help and support. In her book, Enemy Feminisms, Sophie Lewis also described how the nuclear family sets up the father and children in opposition to the mother:

In our middle-class nuclear household, the father scapegoated the mother, and we all ganged up on her: a somewhat rational strategy since, as anti-psychiatry activist and radical feminist Bonne Burstow writes, ‘identification with mother means drudgery and powerlessness.’6

In The Will to Change, bell hooks sets up the father in opposition and in domination of the mother and children. Her advocacy for changes to the nuclear family in less incendiary, less polemic than Sophie Lewis’. hooks described how men are incentivized through the nuclear unit to believe that domination is an expression of masculinity, and an expression of their inherent privilege. In leaning into that, men also lose their ability to be in touch with their emotions. hooks advocates for replacing this model — the dominator model — with the partnership model. Instead of the domination and discipline of the nuclear family model, ideas of “goodness” are based in caring for others and in emotional intelligence.

An Alternative Child-Rearing

I’m going to end with the story of my birth and early childhood here, because it has bearing on the points I’m addressing in this essay. I was born to young parents who had an arranged marriage…and born two days shy of their ten-month wedding anniversary. In other words, my parents were woefully underprepared to be parents.

Despite that, my early childhood had some saving graces. I grew up in a household with my parental grandparents, and my grandmother and two uncles were kind and loving. My grandparents did a lot of childcare: babysitting (thus negating the need to pay for child care, while also ensuring that the care is provided by people who are more motivated to…genuinely care), taking me to doctor’s appointments, teaching me how to tie my shoelaces, getting me a library card and taking me to the library once a week, shielding me from parents who wanted to use physical punishments. My uncle’s girlfriend took on the role of preschool mom, coming to class with me when other classmates brought their biological moms, and driving me to school sometimes. My uncle and his girlfriend also bought me toys, and things like a goldfish tank. I often spent weekends hanging out with them. My other uncle was likely gay (and certainly did not fit into the typical masculine model). He indulged my curiosity, and encouraged my academic interests.

I worked two jobs to put myself through college, and then I went to law school. I was the first college graduate in my family. To this day, the only person who graduated from a non-state/non-commuter university in the extended family. The last time I visited my parents, they said I am the person I am in spite of them. I am the person I am because of the extended family that raised me — especially my grandmother.

I think that’s precisely because I did not grow up in a traditionally American nuclear family. Not all people who can produce a child are equipped mentally and emotionally to provide for a child. “It takes a village to raise a child”. A village can also offset abusive and/or neglectful nuclear family units. I’m so grateful I had that village in those crucial early years.

To go back to something I stated at the end of the first section of this essay: I do not want children anymore. The reason for this is that I feel that I personally lack the support structure to have children. In part because I lack the family unit, nor do I have a tight-unit enough friend group/community to replace that. In part because I don’t have the means/financial success and career I want (yet). Basically, because I don’t have a village. And frankly, I don’t think people should have children unless all of that is in place, and they feel secure in knowing it will continue to stay in place.

Thank you for reading unknown canon. This newsletter is dedicated to intersectional feminist♀️and lesbian ⚢ literature, history, and analysis.

I’ve restricted the comments section on my Substack in an effort to reduce moderation and to make sure that my subscribers/readers feel psychological safe while visiting my page.

If you would like to support this project, please like, share, comment, and if you have the means, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The idea of “economic and societal collapse” goes something like: if you have an aging population, you’ll need young, economically productive people to support that population. Without a healthy birth rate, the young people supporting old people doesn’t work. This is the reason that China did away with the “one child” policy (that the “one child” was supporting two parents and four grandparents in their old age — creating an undue burden on that single child). This is also a reason why the future of Japan and Italy are uncertain — the countries have declining birth rates and less immigration. The US also has a “declining birth rate”; however, the U.S. has historically offset that decline through immigration — and immigrants producing more children.

I’m using “women” to refer to women and people who can give birth to children throughout. Some non-binary and trans men can be included in this; some “biological women” of child-bearing age cannot give birth. I use this terminology not to exclude, but rather to conform to widely-accepted language, and also for ease and readability.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), p. 13.

This is an idea that appears in many feminist and Marxist thinker’s work, eg., bell hooks builds off it in The Will to Change

eg., this is the idea that women of working/lower classes (especially in non-Western countries) are often willing to do the work of carrying children — it’s an analogous argument to sex work.

Lewis, Sophie. Enemy Feminisms: TERFs, Policewomen & Girlbosses Against Liberation. (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books. 2025). p. 7.

thanks Jo for unpacking this problematic agenda. Its particularly galling for me as a queer feminist who was adopted at 30 days old and had my only child abducted for adoption when I was 15. I've just been musing on my stack ( I'm a newbie) about Opting out of Mothers Day and touched on pronatalism as the the new face of empire building, and am adding your great text as a reference.

Thank you for your thoughtful - as always - essay, Jo. You make complex ideas very accessible - so much food for thought. It was lovely to hear about your childhood and very nurturing extended family. Hope you are gathering these columns in preparation for a book!!