The Love Letters of Literary Lesbians

Virginia Woolf, Violet Trefusis, Emily Dickinson, Tove Jansson, Natalie Barney...

unknown literary canon is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to preserving and archiving lesser known literary works, and especially, lesbian literature, poetry, art, and history. if you would like to support this project, please like, share, comment, and if you have the means, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Any and all form of support are deeply appreciated!

When one speaks of lesbian love letters, the first ones, the most famous, are those between Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia1”, Vita Sackville-West famously wrote. Yet, there are so many other beautiful love letters, passionate, beautifully stated, loving and kind … so many lesbians that wrote to their loves that have been forgotten, ignored, or their sexualities silenced.

Here are but a few snippets and their stories, and a few words about the books that are focused on the letters and/or relationships.

First, Vita Sackville-West had an arguably far more intense, passionate love than the adult, mature love with Virginia….

Violet Keppel Trefusis and Vita Sackville-West

Violet [Keppel] Trefusis and Vita Sackville-West met as children, Violet gave Vita a ring and promised her love when they were fourteen, and they began a physical, intense love in their early twenties. About their reconnection as adults, Violet writes:

No one had told me that Vita had become a beauty. She was tall and graceful. The deep eyes of the Sackvilles were like ponds from which the morning mists had risen. A peach would have envied her complexion. She was surrounded by several young men in love.2

Theirs was a deeply passionate romance, the do-or-die kind, the kind that involves running away to Paris, the six-feet tall Sackville-West (not for nothing did Virginia go on and on about Vita’s legs) dressed as a man with a bandage about her head, so that they could openly canoodle on the streets; then there were tears, pleading parents, and threats of disinheritance and disenfranchisement. Violet’s letters, and her words of love, are some of the most beautiful I’ve read. To Sackville-West, she wrote:

You are my lover and I am your mistress and kingdoms and empires and governments have tottered and succumbed before now to that mighty combination.3

and

I am in the act of asking myself if I ought to reply to your question? A question furthermore most indiscreet and which merits a sharp reprimand. Reply, don’t reply, reply! Oh to the devil with discretion!

Well, you ask me pointblank why I love you… I love you, Vita, because I’ve fought so hard to win you… I love you, Vita, because you never gave me back my ring. I love you because you have never yielded in anything; I love you because you never capitulate. I love you for your wonderful intelligence, for your literary aspirations, for your unconscious (?) coquetry. I love you because you have the air of doubting nothing! I love in you what is also in me: imagination, the gift for languages, taste, intuition and a host of other things…

I love you, Vita, because I have seen your soul…4

As is hinted in the letters, Trefusis was the more passionate of the two, there is a note of jealousy, and the relationship made Violet terribly insecure and anxious. For good reason: in the end, Sackville-West later admitted to believing a lie about Trefusis having sex with her husband (Trefusis didn’t) because the relationship and the consequences of a lesbian relationship in that era and for their class were too much for her. Yet, the relationship was seemingly imbalanced, and may have burned fast and furious regardless of whether lesbianism was accepted or not. Sackville-West chose comfort, her family’s money, and her safe lavender marriage. The fall out and consequences were dire for Trefusis, whereas Sackville-West was relatively unscathed.

Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf

Perhaps one of the most famous literary lesbian couples of all time, they need no introduction. Woolf wrote Orlando for Vita, giving Vita back her beloved childhood home (that she could not inherit as she was a girl). Vita’s son call it “the longest and most charming love letter in history”. It’s more than that: a giddy, mischievous book that both glories in the main character’s beauty, enormous charm and charmed life, yet slyly poking fun of her intelligence, her writing skill, and captures some of Virginia’s pain about Vita’s unfaithfulness. Vita and Virginia met at a dinner party, Vita fell for Virginia immediately, Virginia came around a bit slow, and they were together - or separated, writing long, passionate letters - to each other for ten years. After their relationship ended, they remained close platonic friends.

The quote in the first paragraph comes from a letter written by Vita:

Thursday, January 21, 1926

I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia. I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way. You, with all your un-dumb letters, would never write so elementary phrase as that; perhaps you wouldn’t even feel it. And yet I believe you’ll be sensible of a little gap. But you’d clothe it in so exquisite a phrase that it would lose a little of its reality. Whereas with me it is quite stark: I miss you even more than I could have believed; and I was prepared to miss you a good deal. So this letter is just really a squeal of pain. It is incredible how essential to me you have become. I suppose you are accustomed to people saying these things. Damn you, spoilt creature; I shan’t make you love me any the more by giving myself away like this—But oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly. You have no idea how stand-offish I can be with people I don’t love. I have brought it to a fine art. But you have broken down my defences. And I don’t really resent it …

Please forgive me for writing such a miserable letter.5

Virginia Woolf also very much admired Vita’s body: “As a body hers is perfection”, and in her diary, she compared Vita’s legs to beech trees. In Orlando, there are a few deeply admiring, downright funny scenes in which Virginia writes rapturously of Vita stand-in’s legs (again). Her reply is characteristic of her writing; with its sly humor, sharp observation, economy and restraint of emotion, yet warm and loving.

Your letter from Trieste came this morning—But why do you think I don’t feel, or that I make phrases? ‘Lovely phrases’ you say which rob things of reality. Just the opposite. Always, always, always I try to say what I feel. Will you then believe that after you went last Tuesday—exactly a week ago—out I went into the slums of Bloomsbury, to find a barrel organ. But it did not make me cheerful … And ever since, nothing important has happened—Somehow its dull and damp. I have been dull; I have missed you. I do miss you. I shall miss you. And if you don’t believe it, you’re a longeared owl and ass. Lovely phrases? …

But of course (to return to your letter) I always knew about your standoffishness. Only I said to myself, I insist upon kindness. With this aim in view, I came to Long Barn. Open the top button of your jersey and you will see, nestling inside, a lively squirrel with the most inquisitive habits, but a dear creature all the same—

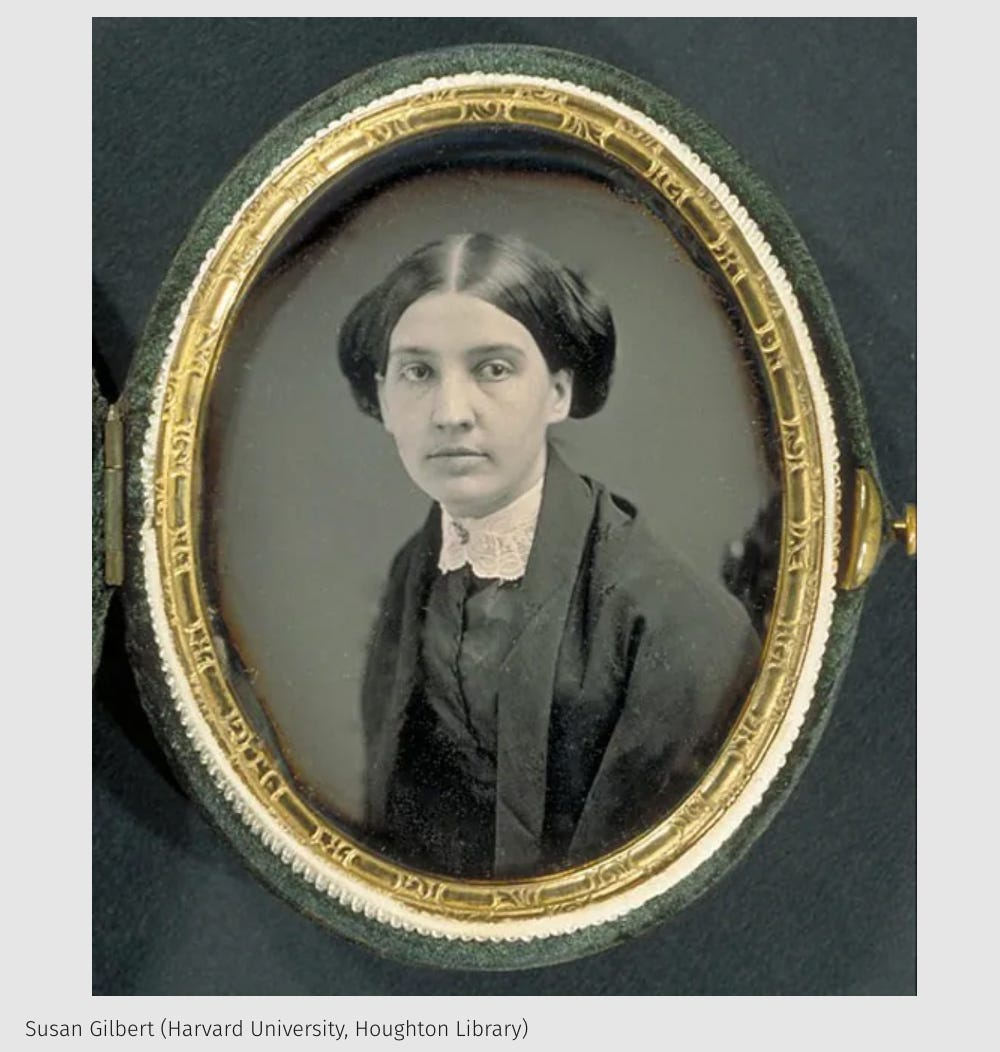

Emily Dickinson and Susan Gilbert, and Maria Popova’s Figuring

Maria Popova (of The Marginalian, formerly Brain Pickings) has uncovered the homosexual loves of many famous artists, scientists, writers, mathematics, and the like from over the centuries. I’m tempted to add her to my “lesbian literature” archive, but she doesn’t speak very openly about her sexuality. One might infer, not only by her interest in the subject but the way she wrote of a a constellation of freckles on her arm, and writes about one particular woman repeatedly on social media.

I read and fell in love with her blog many years ago (she is one of my favorite bloggers), and with her book, Figuring. I read the book during quarantine, when the world felt bleak and hopeless…and it was a perfect choice in that Popova writes about inspiring folks, their art/work and ingenuity, fall in and out of love, face romantic and sexual rejection, and overcome various trials and tribulations. That’s especially true of the many pioneering women she includes, as they overcome social misogyny and misogyny in their chosen fields. In Figuring, she weaves together the biographies of many interconnected pre-Victorian, Victorian, and Edwardians. It reads easily and naturally, though perhaps a little long-winded, sentimental, and flowery for people who do not appreciate that style.

Some of the homosexual affairs and loves she writes about are speculative, as it was dangerous and (for men, especially) illegal to be open about homosexuality. Yet, we know history has tried, even in the face of mountains of evidence (romantic letters, shared hotel rooms, cohabitation) to deny homosexual love and gay/lesbian identity, even deny it when that type of evidence would have been affirmation for a heterosexual love. That denial implies some sort of greater shame in homosexuality and acceptance of heterosexuality. Popova’s voice and work is a force in working against that, and in normalizing queerness.

Some examples of Popova’s speculations from Figuring include Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville, with the older Hawthorne and younger Melville corresponding for mentorship, save that some of their correspondence had strong homoerotic overtones. Hawthorne’s wife, Sophia Peabody, likely chose Hawthorne over Ida Russell, her (possible) lady lover. Ida Russell may have been a lover of pioneering astronomer Maria Mitchell.

To Russell, who died at only thirty-six, Mitchell wrote:

“Take me, lady, spurn me not; this blessing grant me,” Mitchell wrote. “To mingle yet my life with thine, and e’en be one with thee.”6

Popova writes at length about Emily Dickinson, both on her blog and in Figuring. Many passages of Emily’s letters to Susan Gilbert. Susan became a friend to Emily and Emily’s brother around the same time, and both brother and sister fell in love with dark-eyed, androgynous Susan.

To Susan, Emily wrote:

I chose this single star

From out the wide night’s numbers—

Sue—forevermore!7

When Susan took a teaching post that separated the two for ten months, Emily wrote desperate letters that both feared and exuberantly celebrated her feellings for Susan. Weeks before Susan was to return, she wrote:

When I look around me and find myself alone, I sigh for you again; little sigh, and vain sigh, which will not bring you home.

I need you more and more, and the great world grows wider… every day you stay away — I miss my biggest heart; my own goes wandering round, and calls for Susie… Susie, forgive me Darling, for every word I say — my heart is full of you… yet when I seek to say to you something not for the world, words fail me… I shall grow more and more impatient until that dear day comes, for til now, I have only mourned for you; now I begin to hope for you.8

Another interesting point about Emily’s letters that Popova points out is the gender ambivalence she expresses, sometimes calling herself a “boy” or “brother”. Most clearly:

Amputate my freckled Bosom!

Make me bearded like a Man! 9

As Emily became less secure in their love, she wrote:

I would nestle close to your warm heart…Is there any room for me, or shall I wander away all homeless and alone? 10

In the end, Susan married Emily’s brother. All was not lost, because that meant they stayed near, with only a “well worn” path between their houses. Emily and Susan continued to exchange letters through the decades that followed.

Tove Jansson

I recently read and wrote about Tove Jansson. Labora et amare begins the introduction to Tove Jansson’s Fair Play (1989). It’s a personal motto that Jansson worked into her bookplate design, a motto that encapsulates the central theme of Fair Play. Jansson’s far more famous for her children’s books, about the Moomins (imaginary white hippopotamus animals) than she is for her novels for adults. The blurbs of Jansson’s books claimed she lived alone, but in reality she was a lesbian (or bisexual?) and had a long-term relationship with a woman.

After reading Fair Play, I found Letters from Tove (published 2014) at the San Francisco bookshop I frequent most often. Tove was born during World War I, and lived through World War II. She was close to her family, writing many letters while she was away studying. She wrote letters to her friends and lovers also. The letters are as wonderful as her books and her Moomintrolls: concise turns of phrase along with a sort of giddy, child-like joy and constant astonished happiness even in dire circumstances. Tove was in a long-term relationship with a man when she met Vivica Bandler. She introduced Vivica to her close friend, Eva Konikoff. To Eva, Tove wrote:

Another group that’s few in number is the lesbians. The ghosts as we call them - and as I shall call them in my letters from now on. That might be one of the reasons why Vivica attracted people’s attention. It seems to me that the world is full of women who men don’t satisfy their need for affection, eroticism, understanding, etc. Lots of things a ghost can provide - though she can rarely provide respectable security and is over-sensitive.11

In the letter, she wrote that she hasn’t “made her decision” but she’s happy with Vivica. In the letter, she wrote that she was afraid she’d not be able to find other lesbians or find love (Vivica didn’t live in the country). To Vivica, she wrote:

“Never before have the desires of my heart won out over my work, never before have promises been swept aside. It isn’t Paris I’m yearning for. It’s you.”

In the next letter to Eva, Tove wrote that she had decided to live as a lesbian. Despite the passion (or perhaps because of) of her relationship with Vivica, it was short-lived (three weeks or so). They remained friends for decades.

In 1955 (when Tove was forty-one), she met the love of her life, Tuulikki Pietilä (who was three years younger). For all those who might feel hope is lost if you do not fall in love young: Tove and Tuulikki were together for over forty years, and the love reflected in Tove’s letters and Fair Play sounds passionate yet calm and stable, full of mutual understanding and forgiveness. Tove and Tuulikki (their names are so adorably alliterative) lived separately-together, with apartments on either side of a building in Helsinki, and smaller cottage on a rocky island by the sea. Homosexuality was illegal in Finland until the early 1970s; yet, Tove’s letters reveal how much calmer and more stable love is when they can be relatively open about it (as compared to the intensity of forbidden love in the earlier letters). Their families knew; Tove and her mother fought yet remained close when Tove chose to travel with Tuulikki instead of traveling with her mother (meaning: their families knew).

When they were separated (for work), Tove wrote:

Beloved,

I miss you so dreadfully. Not in a desperate or melancholy way, because I know we shall soon be with each other again, but I feel at such a loss and just can’t get it into my head that you’re not around any more. This morning, I put a hand out to feel for you, then remembered you were there, so I got up very quickly to escape the emptiness.12

She ends the same letter with:

Whenever I go on the island, you’re with me as my security and stimulation, your happiness and vitality are still here, everywhere. And if I left here, you would go with me. You see, I love you as if bewitched, yet at the same time with profound calm, and I’m not afraid of anything life has in store for us….Now I’m going to read Karin Boye and then go to sleep — good night beloved.

That is the passage that inspired me to write this post. Tove so simply captures the type of love that lasts a lifetime: secure, calm, built over a shared life, yet still full of amazement, enchantment, and passion.

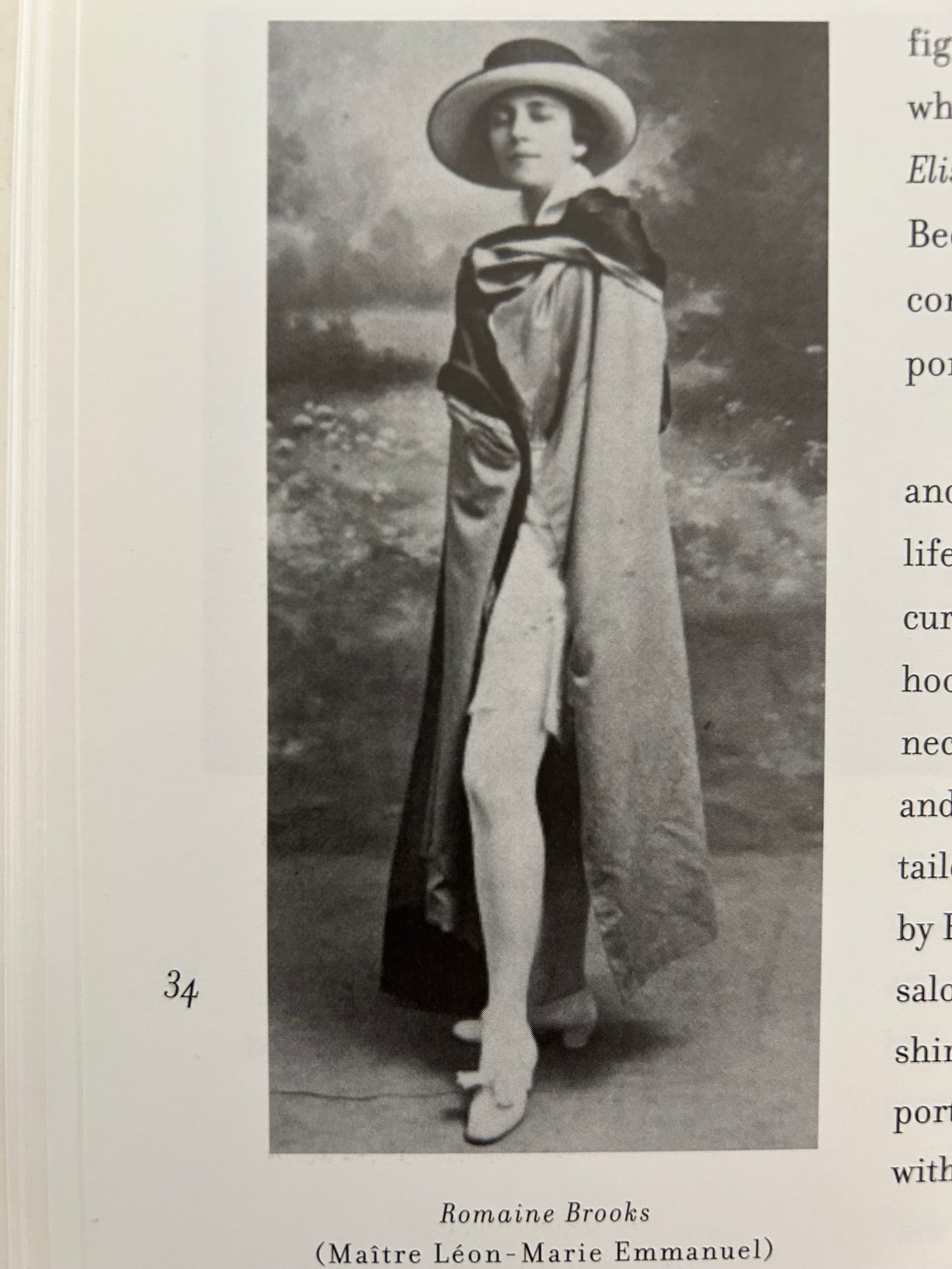

Natalie Barney on Romaine Brooks

That’s a photo of Natalie Barney from the 1910s.

Natalie Barney was a famous fin de siecle lesbian. Heiress, writer, ran a very famous salon, and was very famously a very open, very non-monogamous lesbian. I’ve reviewed her life and one of her books here.

Barney’s memoirs Adventures of the Mind, were published in 1992 by The Cutting Edge: Lesbian and Life, by New York University Press. The purpose of the series was to make available classic lesbian literature more readily available. Much of what was available at the time (through the early 1990s) was pulp. Carol Seajay, who ran the lesbian/Feminist San Francisco bookstore Old Wives Tale, said that in the 1970s, lesbians would pass around pulp novels and warn each other not the read the last chapter (publishers required last chapter to be tragic - written in to “punish” the lesbians for their non-conventionality and lack of adherence to heteronormative morals)13.

Barney’s Adventures of the Mind is a strangely episodic book: each chapter is titled after a person in Barney’s life. Each chapter is made of letters (including from Marcel Proust and Rainer Maria Rilke) and essays. The essays capture Barney’s greatest strength as a writer: her sharp perceptiveness, her ability to honestly capture a person’s characters in a few pages, such that the reader can imagine their reactions and predict their actions much more easily.

Adventures… includes an essay Romaine Brooks (I’ve written about Brooks here, “The Female Gaze”). Another late-in-life love inspiration: they met in when they were in their late thirties or early forties, and remained lovers for over fifty years. In one letter to Romaine (from Diana Souhami’s Wild Girls: Paris, Sappho, and Art: The Lives and Loves of Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks (2004)), Natalie wrote of a time when Romaine wore a bathing suit to an Italian beach. To Natalie, there was no doubt everyone was fascinated and drawn to Romaine’s beautiful body. They were about close to fifty years old then; the physical attraction so strong even a decade or more into their relationship.

Barney’s essays captures Brooks with so much forthrightness, humor, admiration, and love that her words are as beautiful as any letter:

“She is a foreigner everywhere.”

And, in fact, Romaine Brooks belongs to no time, to no country, to no milleu, to no school, to no tradition, nor is she in revolt of these institutions, but rather, like Walt Whitman, neither for nor against them — she does not know what they are. She is the epitome — the “flowery summit” of a civilization in decline. Almost a subconscious psychologist, she puts on her canvases the best kept secrets of the distinctive personalities she paints. She operates on them, relieves them of existence through a confession so strong and so delicate that they themselves are won over to it.14

And later:

She has within her no unkindness, no malice, but when her hypersensitivity makes others suffer, it is only her way of expressing her own suffering.

A statement that shows an enviable gentle understanding and sympathy. She also says:

She is of an integrity, of such a moral purity that she throws the blemishes of others into relief.

Michael Field

“Michael Field” was a Victorian lesbian couple. An aunt-niece lesbian couple15, one whose family and friends accepted their relationship, which began when the aunt was forty-one, and her niece twenty-six. Their project is interesting: they wrote together. They produced poems and plays, and they kept a joint diary running to nearly a thousand pages together. At times, they said they could not tell who wrote which parts. Katherine Harris Bradley, the aunt, was loyal to her sister’s child. Edith Emma Cooper was fifteen years younger, and sometimes fell in love with men, yet stayed with her aunt until her death (she passed mere months before Bradley). Carolyn Dever has written about them in Chains of Love and Beauty (2022), and she’s also given us a shortened, readable version of their diary in One Soul, Divided (2024).

Like Emily Dickinson, Edith sometimes used male terminology and nicknames to refer to herself16. Both Edith, Emily, and others like Radclyffe Hall show how difficult it is to separate sexuality from gender; or to separate “lesbians”, “bisexuals”, “genderqueer”, “non binary”, “androgynous” and “trans” because they’re so closely woven together.

Because they wrote no letters to one another (instead writing as one person), I share a poem by “Michael Field”. To write as one is love letter in and of itself, a testament to the depth of their shared love and understanding.

A Girl, by Michael Field

A Girl,

Her soul a deep-wave pearl

Dim, lucent of all lovely mysteries;

A face flowered for heart’s ease,

A brow’s grace soft as seas

Seen through faint forest-trees:

A mouth, the lips apart,

Like aspen-leaflets trembling in the breeze

From her tempestuous heart.

Such: and our souls so knit,

I leave a page half-writ —

The work begun

Will be to heaven’s conception done,

If she come to it.

conclusion

This is, of course, just a selection of lesbians who wrote letters, and just a small selection of the many letters that exist from the writers who wrote them.

About the letters of Virginia and Vita, Alison Bechdel wrote:

It would be remiss of me not to observe that letter-writing, with its friction of nib on paper, its pace slow enough to allow for the formation of actual thoughts, has fallen out of fashion. If Virginia and Vita had had smartphones, what a stream of sexting acronyms, obscure emoji (Scissors? A Bosman’s potto?), Twitter links to TLS reviews, and endless snapshots of alsatians and spaniels would sift through our fingers in lieu of this magnificent paper trail. But fortunately for all of us, they wrote, and wrote, and wrote, even as their feelings shifted over the years from passion to something quieter. Their letters are ardent, erudite, moving and playful. They are filled with gossip, desire, jealousy and tips on craft. And perhaps most delightfully, they are frequently laugh-out-loud hilarious.17

After I wrote this, I noticed that mature lesbian affairs (Virginia Woolf, Katherine Bradley, Tove Jansson, Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks were all in the very late thirties or early forties when they fell in love with their respective letter writing partner) had high success rates of becoming long term, stable relationships. The younger couples (Vita and Violet, Tove and Vivica) were less stable, more emotionally fraught.

There’s something beautiful about the slowness of the format of writing letters on paper with a nibbed pen. There’s also something beautiful about slow love that many of these writers wrote about, about gently allowing love to come in one’s life, and develop over decades of togetherness.

EDIT: I’ve started receiving some trolls posting defamatory, libelous comments about me in their notes. Going forward, comments will paywalled to help prevent this.

Sackville-West, Vita, and Woolf, Virginia. Introduced by Bechdal, Alison. Love Letters of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. (New York: Vintage Classics.) p. 44.

Trefusis, Violet. Don't Look Round: Her Reminiscences. ed. Hutchinson. (New York: Viking, 1992) p.70

Trefusis, Violet Keppel; Leaska, Mitchell Alexander. Violet to Vita: the letters of Violet Trefusis to Vita Sackville-West, 1910-21. (New York: Viking Adult, 1991).

There’s an excellent Edwardian Sapphics blog that I’ve read through, by Helen Nera. It’s called Les Faunnesses, and it’s in French. She details the affair between Violet and Vita thoroughly, her sympathy too clearly lies with Violet. Link

Ibid.

Sackville-West, Vita, and Woolf, Virginia. Introduced by Bechdal, Alison. Love Letters of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. (New York: Vintage Classics) p. 44.

Popova, Maria. Figuring. (New York: Vintage Books, 2020) p. 52.

Ibid. p. 313.

Ibid. p. 315.

Ibid. p. 320

Ibid. p. 316.

Jansson, Tove. ed. Westin, Boel & Svensson, Helen; trans. Death, Sarah. Letters from Tove. (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2014) p. 239

Ibid. p. 332.

Sullivan, Elizabeth. Carol Seajay, Old Wives Tales and the Feminist Bookstore Network: A Historical Essay. https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Carol_Seajay,_Old_Wives_Tales_and_the_Feminist_Bookstore_Network

Barney, Natalie. Trans. and Annotations by Gatton, John Spalding. Adventures of the Mind. (New York: The Cutting Edge: Lesbian and Life Series, by New York University Press, 1992) p 180-182.

Yes, I find this questionable, mostly in that I have questions about what we’d call grooming. Yet, they remained together for years. I also wrote some of my thoughts on age-differential relationship in an essay about the lesbian boarding school trope:

This isn’t transgenderness per se (it could be, they’re not around to tell us if it does). Lesbians also use “boy” and “boi” and similar language with one another (as gay men call each other “girl” and other feminine language). The use of this language shows the closeness of sexuality and gender, and how the lines aren’t cleanly drawn into neat binaries.

Bechdel, Alison. As a body hers is perfection': Alison Bechdel on the love letters of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. The Guardian. February 1, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/feb/01/as-a-body-hers-is-perfection-alison-bechdel-on-the-love-letters-of-virginia-woolf-and-vita-sackville-west

This is my Roman Empire thank you

i truly enjoyed reading this! love this so muchhh!!