The Coming Out Stories of Literary Lesbians

My story, and a series of lesbian coming out novels

“But the true feminist deals out of a lesbian consciousness whether or not she ever sleeps with women.”

Audre Lorde

My Story:

I vividly remember the first time I had sex with a girl. Though that technically wasn’t the first time; I’d hooked up with girls who were curious, gingerly touching them knowing they wouldn’t touch me back, settling because something was better than nothing. No, this time and girl were different. Weeks before, I had gone to her birthday party. When almost everyone else had gone home, we ran naked in the rain to her parent’s hot tub. Then after a dinner, we came back to my tiny first apartment. A slow dance…

I knew I liked girls since the first blush of sexuality. I remember dreaming about women. I thought it was strange - especially because I was dreaming of grown women, not girls - and felt guilty for it. And noticing women but not men. For a period, I wondered if I was asexual, since I never had the crushes on boys or celebrities that most girls did. Later, I dated a man, but I told him I was bisexual. I met the girl in the story above while he and I were together. Some of our friends were horrified; my girl friends thought being with a girl was “gross”. It didn’t matter to me that they did. It also didn’t occur to me that I had to option of not being attracted men. Besides, men offered things outside of sex: normalcy, safety. We split up. I had been too young for such a serious relationship, or at least, I didn’t really know who I was. Learning that was a process, full of set backs because of added, external circumstances.

Realizing I only liked women hit me like a lightning bolt. Once I thought it, I knew it to be true, and that truth hasn’t altered or wavered. It only brings me joy, I feel no hesitation or awkwardness. Do I doubt my queerness? No, not at all. Do I question if I’m “gay enough”? Nah, though that’s very common amongst gay folks. Do I look gay? Yeah, I think so. I don’t know why, but somehow it feels right and important. Actually, if I think about about being a lesbian, it makes me want grin. It feels like the best thing a woman could possibly be, I don’t understand why anyone would hate me for being so.

I lost a few friends, mostly men who made terrible “jokes” that betrayed their negative opinions of lesbians. I gather because bisexuality (and sexual available to men) is more acceptable than lesbianism (and sexual unavailability to men, and generally men are adapted to receiving more attention in society, ).

Tolstoy famously wrote “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Nah, my family is deeply unhappy in a very typical way: alcoholism, depression, the accompanying dysfunction and emotional abuse, religion, and ignorance. Coming out was easier for me since I don’t have any sort of relationship with them; easier than it is for any of the queer Indian-Americans I’ve spoken to about their stories. My story is relatively easy, it’s other parts of my life that have been more harrowing.

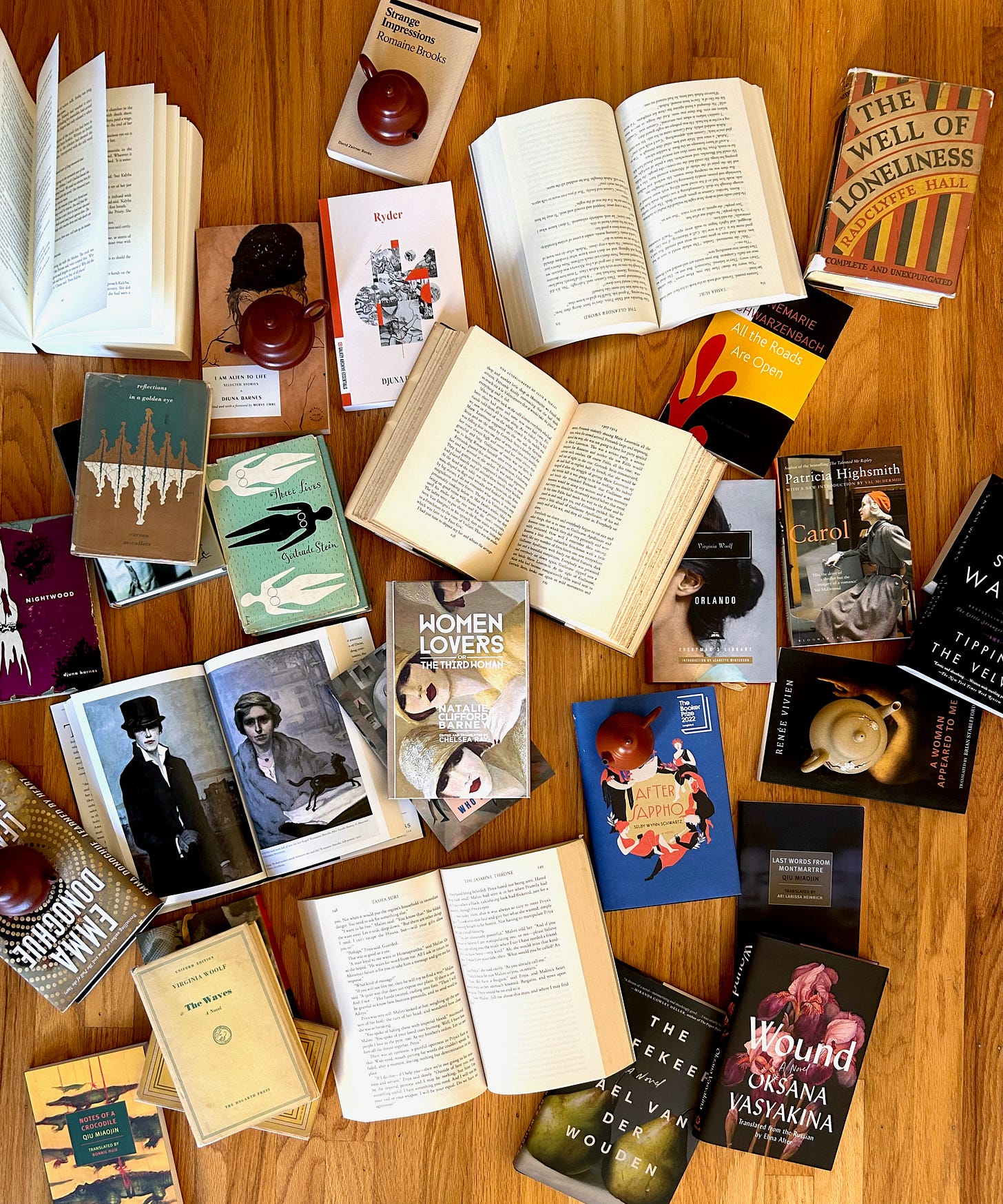

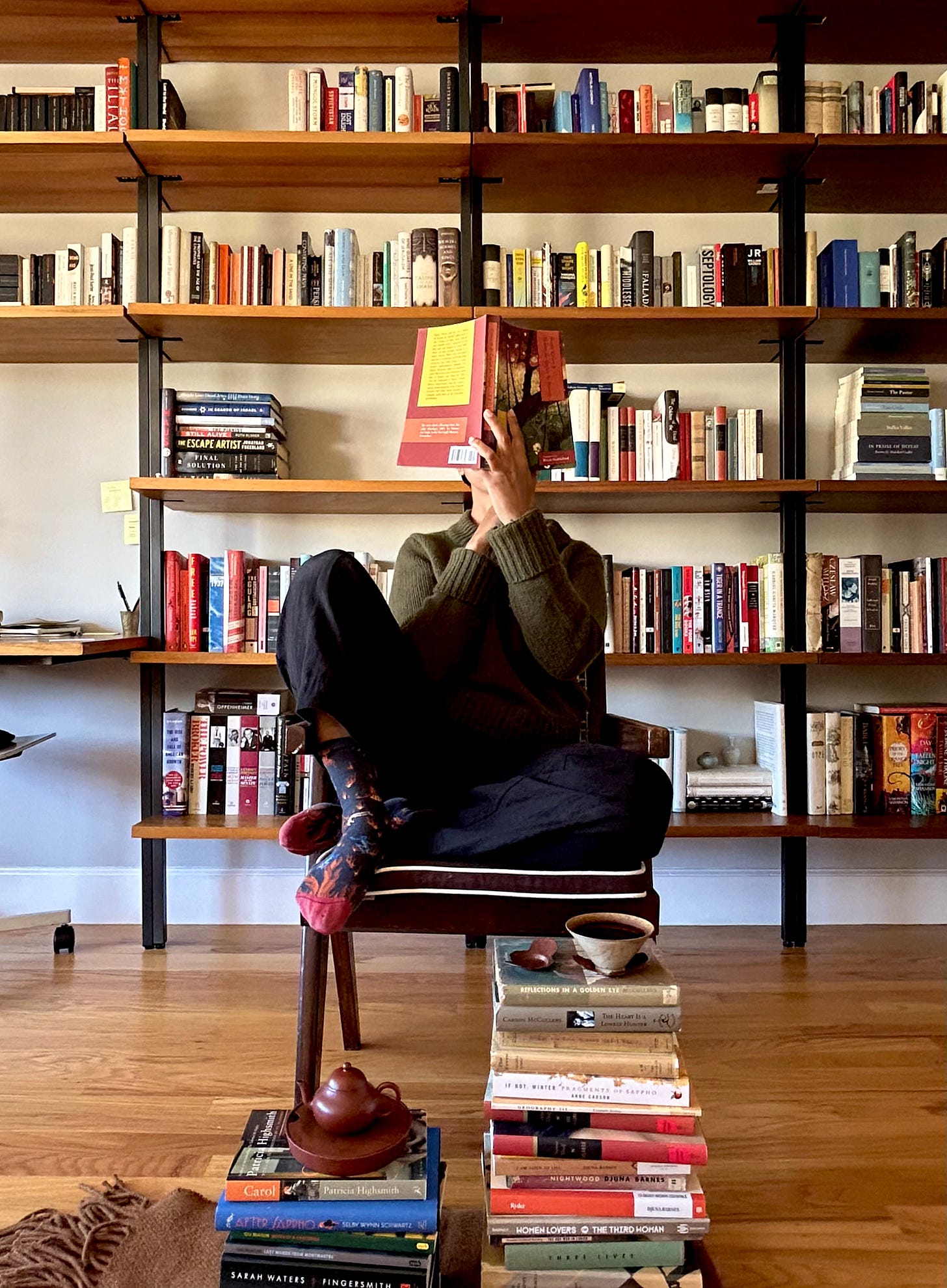

Needless to say, but I’ll say it anyway: the queer experience varies for everyone, and stories of coming out run the gambit. Here, I present to you a collection of lesbian novels and memoirs that include coming out. I’ve written longer reviews of every one of these except the first; you can use look through the lesbian literature tab to find them (alphabetized by author’s last name, so it should be pretty easy). I end this piece by touching upon the Audre Lorde quote above: telling you why I believe lesbianism and lesbian stories are important for all feminists, and how lesbians serve as living examples of prioritizing self and womankind.

unknown literary canon is a reader-supported newsletter dedicated to preserving and archiving lesser known literary works, and especially, lesbian literature, poetry, art, and history. if you would like to support this project, please like, share, comment, and if you have the means, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Any and all form of support are deeply appreciated!

Chloe Caldwell’s Women: A Young Woman Coming Out

The story that inspired this piece is Chloe Caldwell’s Women. This is a book that in both its foreword and Caldwell’s afterword continually tells the reader of its importance. How instrumental it was for women coming out, as Caldwell wrote out fan mail letters in her afterword.

That said a lot about the author. The book is seemingly autofiction; the story of a young woman who is pursued by a lesbian who is nineteen years older and has a long term girlfriend. The young woman has only been with men, the crush dawns on her slowly. They have sex, way more sex scenes than other lesbian-written books I’ve read. They have a lot of sex, with the older lesbian pleasuring the younger one only. It’s intense and dramatic, with dozens of daily emails (this is because Caldwell smashes her phone in a fit of anger), and lots of loving statements that also carefully avoid true commitment. It’s a fairly standard toxic relationship, with Caldwell as the anxious one and Finn (the older lesbian) the manipulator (predictably, as she’s older, far more experienced, and is lying to her long term girlfriend to be with Caldwell).

It’s only in the latter third or so that Caldwell begins to question her sexuality. She comes out to her parents, asks her friends if they knew, shops for new clothes (even though she has no money), and goes on a series of failed dates with other women. Finn keeps asking Caldwell to take responsibility for her part, that the situation was created by both of them. That’s both fair and unfair.

The novel has two great weakness. One, while it uses a lot of self-help and therapy-speak (and ravishing reviews from other authors who do the same, eg, Cheryl Strayed), Caldwell herself doesn’t take personal responsibility or develop self-awareness. She not only continued to date someone who repeatedly told her she’d not leave her girlfriend, but she implies helplessness around her decision. The ending feels abrupt, charting a relationship with minimal emphasis on coming out or identity, thus turning lesbianism into merely sexuality and sex. Second, there’s little joy or happiness in this novel: Caldwell goes from passion and sex, to sadly exploring her sexuality and going on failed dates, the sad, slow demise of a relationship that wouldn’t never last, then it ends on a confused note.

Constance Debré Playboy and Love Me Tender: A Midlife Woman’s Coming Out

I chose after and before pics of Debré….mostly because I found it the contrast in how much more comfortable she seems in her own skin (even though she’s in her French lawyer’s robe) in the former photo. Weirdly enough, my hair journey was similar: shoulder-length/bob, and now it’s not shaved but fairly short. Almost every lesbian I know is obsessed with hair, we talk about it a lot. I think because it has so much to do with gender presentation and how we present ourselves to the world and think of ourselves.

Debré’s life story has similarities to mine, although our coming out stories are not the same. She’s also an excellent, original writer, following the lineage of French queer autofiction authors including Hervé Guibert, Guillaume Dustan, a bit of French-American Natalie Barney1.

Debré was married to a man, both of them were a practicing lawyers, had a son, lived a very bourgeois life in one of Paris’ most expensive neighborhoods. Her great-grandfather was a pioneering pediatrician with hospital wings named after him, her grandfather a French prime minister, her mother a model from an aristocratic family.

Debré falls for the mother of one of her clients. She abandons her life, says the back of Playboy, but I think she threw away her life - husband, legal career, money and nice things - to become a lesbian. In an interview, she said she realized she’s a writer the same week as her first sexual experience with a woman. Her first affair with a married woman who’s a decade older, then another with a girl she’s known since childhood that’s fifteen years younger.

Her son grows increasingly angry with her, as does her ex as it occurs to him that this isn’t a phase and Debré wants a divorce. Her husband drags her through the legal system over custody, even though Debré has already agreed that their son will primarily live with his father. She has little choice about custody: she has very little money or stability, she wasn’t in the position to support a child anyway. She fully owns her choice to run away from her old life.

Debré doesn’t spend time feeling pity for herself. She’s too busy having fun: writing, making friends, figuring out how she’s going to feed herself and where she’s going to sleep, fucking almost any girl that will let her as she grieves the loss of the closeness she and her son once had. She very much accepts that she can’t have it all, and the consequences of her decision. She’s a charmer, full of boyish bravado, and you root for her all the way.

Eileen Myles: Chelsea Girls and Cool for You: A Non-Binary Lesbian Comes to Terms with Her Sexuality

Myles grew up middle class, and dated men when she was young. They makes no bones about enjoying the experience. They knows what she’ll give up when they stop dating men, that lesbians “lack the privileges of men and the protection that accrued from hanging around with them”. As someone who had been raped as a teenager, Myles understood the need for “protection”. This is something lesbians are keenly aware of, Andrea Dworkin wrote about it at length.

Myles, like boyish Debré, never quite fit into the feminine stereotype. Debré wrote that she once talked over liking girls with her (then) husband, Myles tells us that a male lover brought this up to them as well. Myles first realized they were attracted to women, then eventually they take a woman home, and keep dating only women.

Myles had a fascinating life, broke lesbian poet who cried out of hunger at time, does a lot of drugs, drinks too much, moves to San Francisco then New York City, wild adventures with women, eventually cleans up, works their way into the highest echelons of their field.

Natalie Barney: Women Lovers, or the Third Woman, and The One Who is Legion: She Who Always Knew

Natalie Barney was the lesbian to know back in the Edwardian era. Her Parisian salon attracted the hottest lesbians and artists (eg, Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and Marcel Proust made it, Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva so bitter that she was never invited that she wrote a whole series of letters to that effect).

Barney was an American heiress, expected to marry well and conform to femininity. She said she knew she was a lesbian as soon as she conceived of the idea, knew she was attracted to women even as a child. As a preteen, she attended a French boarding school run by (likely lesbian) Mlle. Marie Souvestre, which solidified her choice. As a young women trying to escape her controlling, alcoholic father, Barney moved to Paris. She had her first lesbian affair with a girl with long red hair when they were about seventeen.

When Barney published a book of lesbian poems, her father found out, purchased every copy, even purchased the printing plates and had them destroyed. Barney kept writing. Her father died when she was twenty-six, she inherited a fortune, and she kept writing.

Romaine Brooks: Strange Impressions: The Harassed

Barney’s long term lover, Romaine Brooks, might have been bisexual or lesbian. Brooks’ longest, deepest affairs were with women, including a fifty+ year relationship with the aforementioned Barney, and a four year affair with stage actress and heiress Ida Rubenstein. As a preteen, Brooks “fell in love” with a photograph of a beautiful dead nun, had some sort of physical affair with a girl at her boarding school, and befriend gay men in her late teens as she saw a similarity between her attraction to women, and their attraction to men.

Brooks was sexually harassed as the only woman in her painting classes. She was likely assaulted or coerced into sex for money by her brother-in-law. She gave birth to a child, who she had to give up, as she didn’t have money to support the child (she also went hungry at times in her life). When she came into an inheritance, she tried to find the child and was told her baby had passed away.

These are the costs that women pay in an unequal society, and especially lesbians as we don’t have a boyfriend or other male partner to protect us from the harassers and coercers. After those early misadventures, Brooks continued having affairs with women (she and Barney were not monogamous), and became a famous painter of lesbians.

Violette Le Duc: Thérèse et Isabelle and Le Bâtarde: Boarding Schools and Bisexuality

Violette LeDuc grew up the poor and illegitimate. She was very close to her grandmother, who died while LeDuc was a child, and had a close but contentious relationship with her mother.

In both Thérèse et Isabelle and Le Bâtarde, LeDuc describes her earliest affair with a young girl (they’re twelve? fourteen?). At first, these two girls dislike each other, but they somehow connecting, and then in an intense sexual relationship. They’re eventually caught, and despite promises of forever, they never see each other again. LeDuc later has a long term affair with a piano teacher at the school; the teacher is caught and fired.

LeDuc describes these affairs as does Barney: entirely natural, without any awkwardness, questioning of sexuality, torment about identity. When LeDuc presents her (teacher) live-in girlfriend to her mother, there are no scenes or drama.

After the second affair ends, LeDuc marries a man. She was attracted to women still, falling for Simone de Beauvoir, who did not reciprocate her feelings but helped her career enormously.

Tove Jansson: Letters from Tove and Fair Play: The Decision to be Lesbian

Tove Jansson grew up in a close-knit, loving family. She also had several male lovers when she was young. Then, she met a woman that she fell for immediately.

In a letter to a friend about that woman, she wrote:

Another group that’s few in number is the lesbians. The ghosts as we call them - and as I shall call them in my letters from now on. That might be one of the reasons why Vivica attracted people’s attention. It seems to me that the world is full of women who men don’t satisfy their need for affection, eroticism, understanding, etc. Lots of things a ghost can provide - though she can rarely provide respectable security and is over-sensitive2.

Here, she knows she has a decision, and she knows what coming out as a lesbian will cost her and how it will benefit her. It’s a remarkably honest, realistic appraisal, giving in neither wholly to despair nor exuberance. When she decided, she wrote that she “went over to the spook side”, so she became a “ghost”.

Her take that lesbians were over sensitive captures something that a lot of lesbians would tell you: that lesbian affairs tend to be intense and dramatic. This comes up in all the other books and with all the other lesbians I’ve described: broken phones (Caldwell), dozens of late-night text and begging for your lover to take you back (Debré, both has others do it, then once, does this herself), dramatic fights and accusations (Barney and Brooks), strangely insulting yet loving (Le Duc), declarations of love that far too early (the subject of many lesbians jokes). I’ve tried naming this when I speak to women who love women, I haven’t come up with a satisfactory answer or term for this intensity.

Yet, of all of the lesbian love affairs I’ve read of, Jansson’s forty-year love with Tuulikki Pietilä seems the most calm, and consistently understanding and forgiving, a reflection of the way she made her decision to live her life as a lesbian.

What a Lesbian Consciousness Can Teach All of Us

Once we move past Caldwell, a trend becomes obvious: each of these lesbians knew there was a cost to coming out and living as a lesbian, and they were willing to pay that cost. They put up with male harassment, with men using the legal system against them, with rape or coercion. Many of these women lived through a period of dire poverty (Debré, Myles, Brooks, LeDuc), as women on average make less money than men.

Here’s where I think Audre Lorde was going with that quote: lesbians are living a feminist life. The world is one in which women are the center.

The upside of not having male protection is that you are freed of expectations and conformity; there’s an inherent defiance in it. There’s the sexual freedom: to pursue with and have sex with as many or few women as you desire, without the labels of prudish or promiscuity that too often get flung at heteronormative women. There’s practically no risk of unwanted or accidental pregnancy, far lower risk of sexually transmitted infections3, dramatically reduced fears around date rape. It allows you to be a broke lesbian writer, if you chose that. You’re not asked to sacrifice or make your career secondary, in the way society all too frequently asks of women in relationships with ambitious men. It makes you an outcast, but being an outcast frees you from the shackles of expectation of feminine submissiveness. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, which was asked in the Declaration of Independence and granted to men is more readily available to lesbians. That means you might fail, of course, but you’re free to fail. All of this allows you to look at the women in the world, and know what could be. It’s not that it’s all wonderful, but above all, you are free.

Funny coincidence: Debré’s grandfather eventually kicked Natalie Barney out of Barney’s decades-long home.

Jansson, Tove. ed. Westin, Boel & Svensson, Helen; trans. Death, Sarah. Letters from Tove. (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2014) p. 239

Because of the way lesbians have sex, the risk of STIs is much lower; whereas gay male sex puts them at much higher risk. Even bisexual women are more than double the risk for STIs than lesbians…I didn’t save the statistics when I looked up this up two days ago.

“ It makes you an outcast, but being an outcast frees you from the shackles of expectation of feminine submissiveness. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, which was asked in the Declaration of Independence and granted to men is more readily available to lesbians. “

Viva libertad! 💕

Also so many new books added to the list!

I love reading coming out stories for so many reasons - but mostly for that feeling of pure liberation when a person recognizes that all their "choices" up to that point have been mere habit or convention.

I *just* read WOMEN last week and it was so pure and perfect. You know how I feel about Playboy... and thank you for the truly excellent reading list!