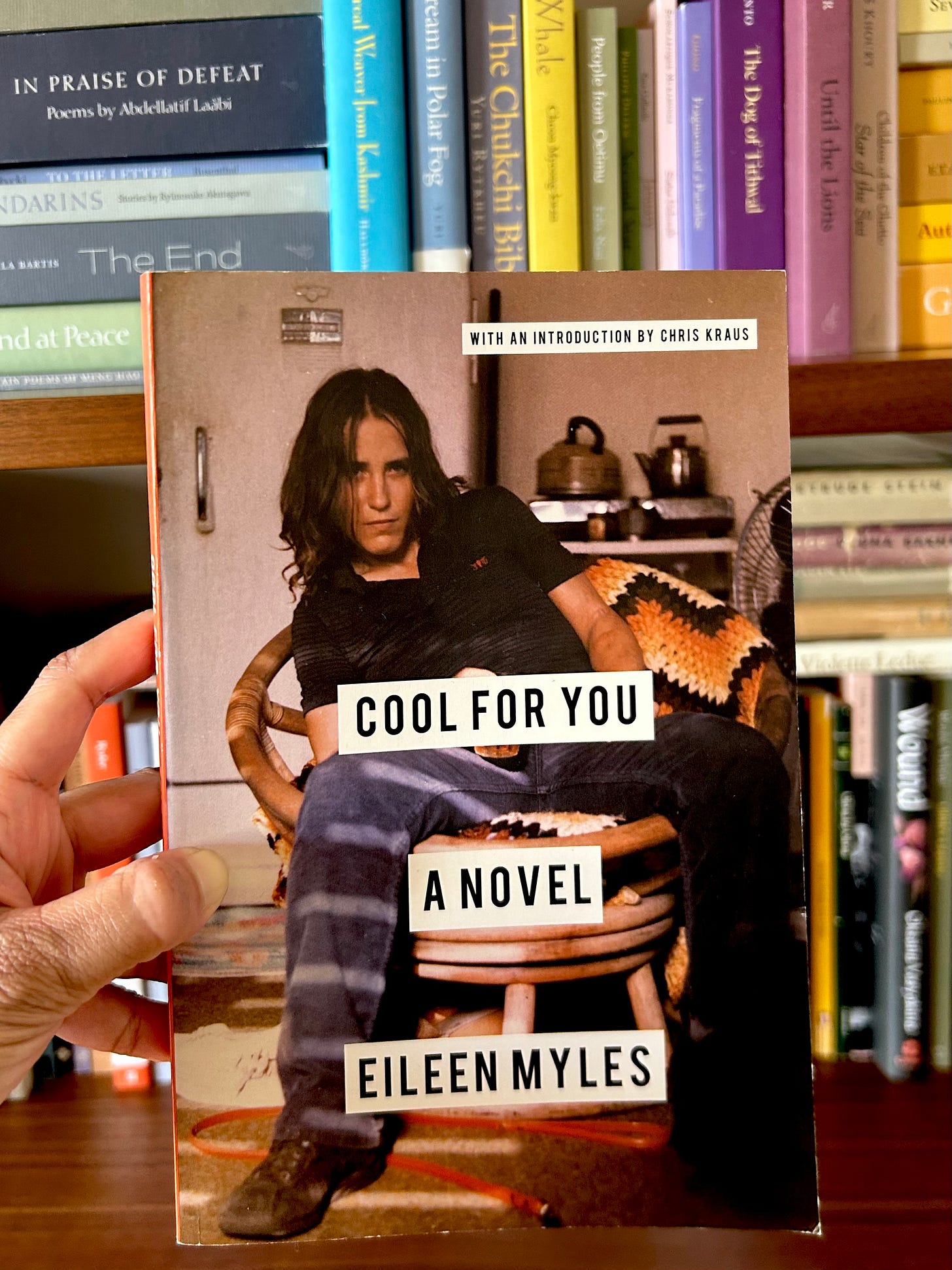

Eileen Myles’ Cool for You

“All the girls in my cabin…had been to Europe. It felt weird. They could swim, they could ski, they had been to France and rode horses. The person most often miscast in my movie is me.” This sentence, from Eileen Myles Cool for You (2000), is a beautiful encapsulation of being working class and being around people who are not. It’s the working class kid and teenager that feels out of place, abnormal, and weird. What a perfect choice of world to capture youth, one of those words we use more often when we’re young and slowly outgrow.

Cool for You was published six years after their more popular Chelsea Girls (1994). In the introduction of Cool for You, Chris Kraus states that she believes the loose-knit, episodic novel is an interrogation of childhood and a künstlerroman1. Cool for You might be that for Kraus. It’s something different entirely for me, and maybe something entirely for other people like me: outside of the establishment. The permeation of class through the experiences Myles details in Cool for You is the theme that most clearly stands out in her work, and through her life. They describes the weirdness, the awkwardness, the small humiliations of poverty. Myles grows up in Boston, dad dies young and was a mail carrier. Their mom’s a secretary. They (Myles uses they/them pronouns) are nearly as in disbelief that their parents house cost about $13,000 (USD) as someone of my generation is. There are the things that are treats for them that the rich kids take for granted and as everyday. As a working class kid myself, I think Myles means middle class or upper middle class; when you’re a working class kid, kids whose parents went went to college, are doctors or lawyers or successful business people are relatively “rich”. If you’re a poor kid, you don’t have much, and your options are limited. A working class kid doesn’t have a pool in your backyard, doesn’t go to Europe, college is the great hope out, but don’t expect anyone say how proud they are of you if you get there.

Post commuter-college graduation, Myles get a job working at Shriver Center. They write frequently of the literal filth; the entrenched smell of human feces and residents urinating on the floor. Another humiliation of the working class; taking on unpleasant, going-nowhere-fast jobs because options are limited and bills must be paid. They drive a cab. They move west, to San Francisco, there are a lot of men around. The stories of being young, of avoiding men but having sex with a lot them, of drinking a lot.

The lesbianism is latent. They experience the first stirrings of same-sex attraction as a summer camp counselor through homoerotic friendships and the “moist heat of sexual imagination” (p 54). They are “[r]eally not a girl anymore. A boy on her bed in the world” (p 100). They mostly date men, but one of those men asks if they prefer women. Eventually, they make it to San Francisco, work more odd jobs, then to New York. If you’ve read Chelsea Girls, or know anything about Myles, this is where they become a successful poet and a lesbian.

On Being Working Class

Here’s a thing that few people today get: being working class isn’t all bad. the way Myles writes it, the dead-end jobs, the drinking, the sex…all the way through Chelsea Girls, which starts off with an arrest and night spent in the drunk tank…it’s an adventure. There’s the sense of the unexpected. Life’s a trickster, who knows what she’s going to give you next. Whatever it is, it’s not boring. Sometime, there’s some bad, cleaning up human feces isn’t the greatest. You know what though? Working 16+ hour days if you want to make it as a lawyer isn’t all that great either.

That’s the thing. There’s no script, so there’s fear and freedom. Myles got to do what they wanted. They sometimes went hungry and homeless, but it was on their terms. They had a sort of control over their destiny, rather than allowing others or “society” to chose it for them. There’s a reason that people try to opt into it. That’s what Constance Debré tries when she gives up her lawyer job and lives the broke-lesbian-writer experience2. Or a very young (heiress) Romaine Brooks, who moved to the island of Capri, lived in her studio, and sometimes went hungry. She later said that was the best time of her life.

On Making It

Myles is famous for her poetry and for being a lesbian; prior to reading Cool for You and Chelsea Girls, I wouldn’t have presumed they grew up working class. It’s weird, that if someone is successful, the presumption has become that they were always middle class. That they were always part of the class they’re currently part of. That was likely always the case: class migrants, to move up or down more than one inflection of class (eg, lower class to working class) doesn’t happen. It’s a statement on the increasing rarity of achieving the immigrant myth of the West and/or the American Dream. In an interview, Myles said:

There’s a fundamental problem in working-class families. It’s like you revere art, you believe in reading, you believe in books, but you don’t understand their production. That’s the disconnect. Those are the keys you can’t have. And that’s the nonlineage that cuts people from other classes out of the art life. Art looks like a lottery from out there.

….

I have made myself homeless. I have cut myself off from anything I knew prior to living in New York. I did this to myself, so I know exactly how it happened. Yet in the poetry world, people need to act like they don’t know how this happened. Like a je ne sais quoi, but it’s them. There’s a faux vernacular, as though the ambition must be hidden at all times, to be more, I don’t know, attractive? It’s the loafer posture, the veneer of I don’t really need this. People loved to talk about how Frank O’Hara didn’t really care about getting published. That doesn’t jibe with my experience.

In that, Myles captures the hardest part of being a working class kid: that if you are ambitious, you don’t have the luxury of making it look easy. It means trying more often, and less certainty. It’s not the amount of work, it’s…well, it might be working dead jobs to pay the bills while also trying to make a go of whatever it is you want to do. Not having the information, or the connections, and not being able to get the introductions you need, and the added work of trying to get those things. When Myles moved to New York City, they began participating in workshops by the St. Marks Poetry Project. The Project promoted working artist; here they met Allen Ginsberg then became an assistant to another poet, and became an artistic director of the St. Mark Poetry Project. Here were a handful of keys.

These were the keys that Violette le Duc was looking for, too. She feared a lack of talent and opportunity would keep her achieving her secret ambition: to become a writer. Her insecurities drove her to becoming an office person at a publishing company…which led to the first key: a close friendship Maurice Sachs. Sachs encouraged her to write while she worked as a black marketeer of farm goods for city folks, and championed her work. This led to another connection and mentorship, Simone de Beauvoir, which yielded a book deal. It’s the story of so many writers, like Annie Ernaux, who taught at a lycee for decades, whose talent and ethic yielded international praise and well deserved Nobel Prize in Literature.

And perhaps, reader, it’s also you. Maybe like me, like the women I’ve listed below, you have an ambition you’re pursuing. As Myles points out, there’s often a lot of shame in admitting ambition, and greater validation in being a flaneur or a dilettante. However, if you’re not part of a leisure class (a phrase that’s gone out of fashion but is still applicable), the process is different. There’s creating and doing the work, but learning the ropes, finding mentors and advocates, maybe working while creating. As Myles shows through both Cool for You and Chelsea Girls, that process can be a lot of fun and bring a lot of joy. It can bring a lot of satisfaction too, maybe more than if it were easy. And that’s a part to remember, and that Eileen Myles’ novels remind of me: that difficult journey is worth pursuing, the price is worth paying, the creations are worth creating.

Artist’s novel; about an artist’s journey to becoming the artist they are.

Debré acknowledges that she’s not working class and that she’s bourgeois. Despite the lack of funds, she likely had more in roads with publishers and knowledge/connections of how to reach them than someone born into the working class. Brooks had a trust fund that she didn’t know about until her mother’s death - it allowed her to create art without worrying about how sellable that art was.

No info no connections. That was me. Immigrant traumatized child holocaust survivor parents. They thought wanting to be a writer was crazy. I was abused as a child and in my first marriage. But I left and eventually sort of figured it out. I never understood how to lean on my agent and editor when I got them in my 40s. But I wrote and my work was published and it was translated into other languages. You can do it and do it better than me by letting yourself make connections and get the info that you missed. You can lean on people and let them support you and your work

This sounds so good. Thank you so much for this thoughtful review! I love the idea that growing up working class means you can’t make it look easy — it strips away a veneer of bs that middle and upper class kids benefit from.