Fair Play, or Labora et Amare

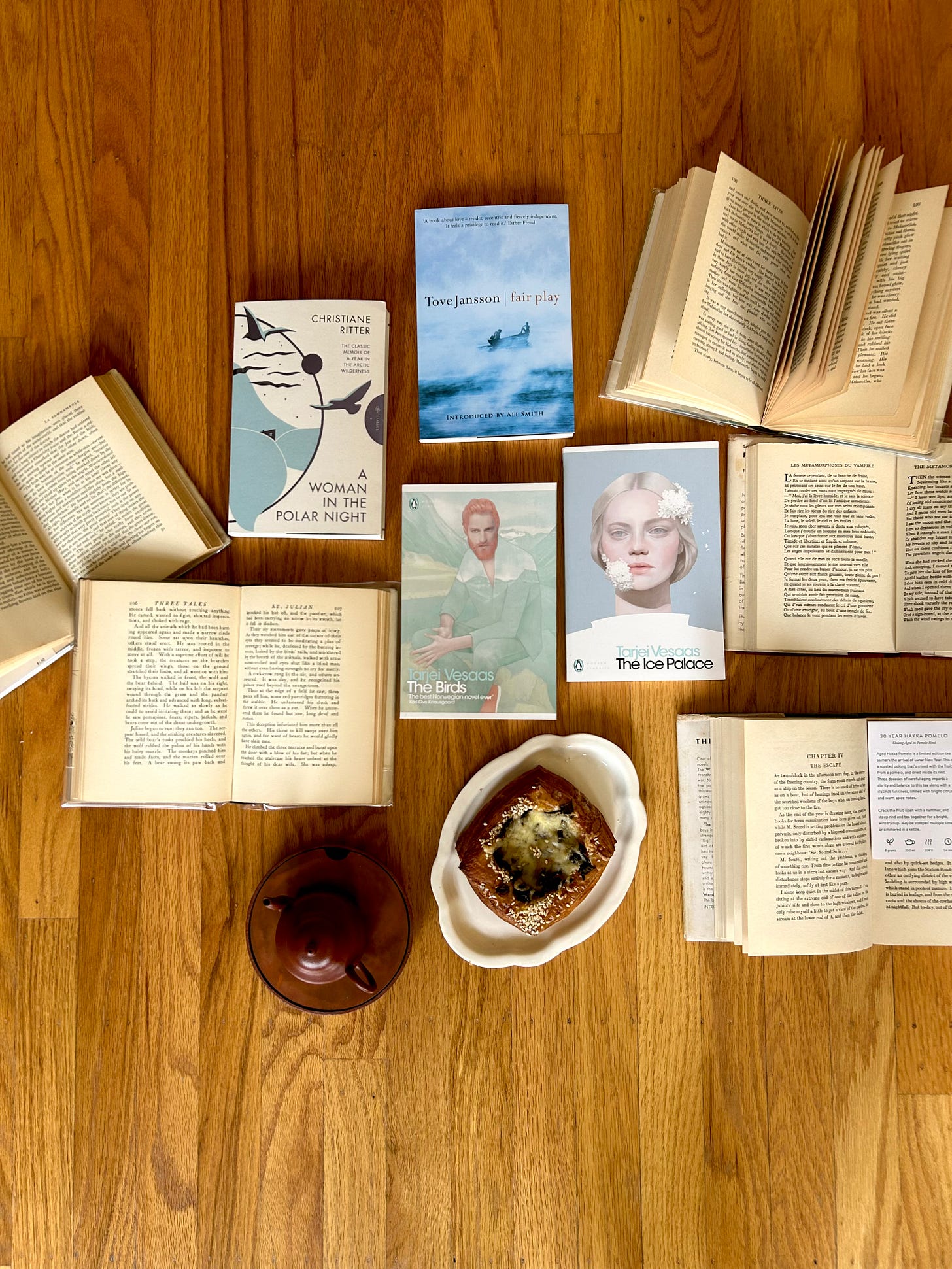

Labora et amare begins the introduction to Tove Jansson’s Fair Play (1989). It’s a personal motto that Jansson worked into her bookplate design, a motto that encapsulates the central theme of Fair Play. Jansson’s far more famous for her children’s books, about the Moomins (imaginary white hippopotamus animals) than she is for her novels for adults. The blurbs of Jansson’s books claimed she lived alone, but in reality she mostly lived with her (female) lover, Tuulikki Pietilä for over forty years. They are pictured below; Jansson is the darker haired of the two.

Fair Play is seemingly autofiction/semi biographical, episodic novel about the lives of, and love between two women, Jonna and Mari. Like Mari, Jansson was a writer and illustrator. Mari and Jonna each have private spaces and studios; apartments on either end of a larger building, but they seemingly share a main room and kitchen. They make art during their days, and meet in the evenings to have dinner together, watch films, talk, or read together in relative silence. They care deeply about their friends, but they prefer evenings of alone-togetherness with one another.

The book is also a primer through example of how to live, or how to live as Jansson saw fit. There’s a graciousness and giving about the novel and the behavior of both women toward one another that feels lacking in our modern self-focused world. The two women argue sometimes, yet never in a way that isn’t repairable or rooted in disrespect. They respect the other’s creative process, almost intuitively. They disagree and feel jealousy, yet they know when to hold their tongues and resolve it internally rather than allowing resentments to simmer. Each listens to the other reminiscence the same memories about childhood, parents, family, hearing stories they already know, knowing that part of partnership is allowing your partner to be repetitive. The first story is about one partner allowing the other to go through a creative process in hanging then rehanging photographs and works of art - patiently allowing the partner to experiment even when she does not fully disagree. Another is the story of an argument that arises over a killed bird, an argument that shows the core differences in personality between the women. Unlike every other lesbian book I’ve read, there’s is no clear implication of sex nor any overt romantic gestures or language, nor anything explicit about their identities as lesbians.

The Plotless Novel

Fair Play is the sort of novels many readers would consider plotless, or “no plot just vibes”. There’s little conflict to be resolved, or if there is, it’s secondary to the character’s thoughts and feelings (eg, Annie Ernaux The Happening or The Most Secret Memory of Men by Mohamed Mbougar Sarr). There’s little cause and effect, nothing on the surface that linearly moves the story in a certain direction. It doesn’t have the action-based excitement and charge of a plot-driven novel, relying on a different set of emotion pulls: joy, calm, anxiety, melancholy, nostalgia, tragedy. It’s philosophical, sometimes drawing directly from specific philosophers (eg, Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Pleasures). Readers of literary fiction will recognize this: it’s autofiction, modernist, stream-of-consciousness.

The Character-Driven Novel

When I was young, I called the type of literature I primarily enjoyed “character driven”. I know the more formal terms for it, but that the novels I enjoy most are driven by character over plot.

Research shows reading literature increases empathy1. It’s reasonable to draw from there that the type of fiction where the reader is placed into the mind and the everyday life is the type that’s more likely to increase empathy. As the reader, you’re getting to know a character that’s not you intimately. The more characters you get to know, the more at ease you become with imagining yourself to be them; putting yourself into their shoes so to speak. Through that process, you, reader, learn to recognize that what makes us all human, that despite our quirks and shallow dissimilarities, the shape of our loves, fears, and dreams, is more similar than different.

This is the core of what I set out to do with Unknown Literary Canon. There are a great many social media accounts, newsletters, newspapers, magazines finding community through reading the same works: the Western classics, the Western canon, and the popular mainstream literary fiction works. Here I offer alternatives for those of us who find community in and empathize with the outcast: the lesbian woman writers (the smallest of the “LGBT”2), the post-feminist women authors, and the non-American. If you scroll through articles and social media posts, you might get the impression that the outcast is something new, that conformity to specific ideals and a lack of empathy for people that don’t fit in was the norm. Reading the century-old and older works that did not conform demonstrates that empathy and acceptance for all existed in many communities and for many people. If reading literature builds empathy, then it’s reasonable to infer that reading literature by authors who don’t conform and are more accepting of all might be a stronger tool in doing so. Fair Play, without plot or action, has a similarity to my project here: to gently guide the reader into acceptance of a life (artistic) and love (between two women) that are unlike the norm, and to show how might not be so different from you and yours.

Bal PM, Veltkamp M. How does fiction reading influence empathy? An experimental investigation on the role of emotional transportation. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055341. Epub 2013 Jan 30. PMID: 23383160; PMCID: PMC3559433.

and

Mar, Raymond A, Oatley, Keith, Hirsh, Jacob, dela Paz, Jennifer, Jordan B. Peterson. Bookworms versus nerds: Exposure to fiction versus non-fiction, divergent associations with social ability, and the simulation of fictional social worlds. University of Toronto, Department of Psychology. September 15, 2005.

According to a Pew Research survey, approximately 8% of Americans identify as LGBT. Of that, over 50% are bisexual, 24% are gay men, 13-14% are trans/genderqueer…and lesbians make up 11%. Because we’re a smaller group, there are fewer of us producing lesbian media (books, blogs/newsletter, art, movies, etc.).

I absolutely loved this article! Your point about how character driven fiction fosters empathy really struck me; it made me reflect on how some of my favorite books have shaped my understanding of others.

As a writer, I tend to gravitate toward this kind of storytelling, but I often worry that my work will feel too 'boring' without injecting high stakes action. Reading this reminded me that action isn’t always necessary to drive a story forward: emotional depth and human connection can be just as compelling. Thank you for this beautifully written and thought-provoking piece!