The Bravery of Russia's Sappho

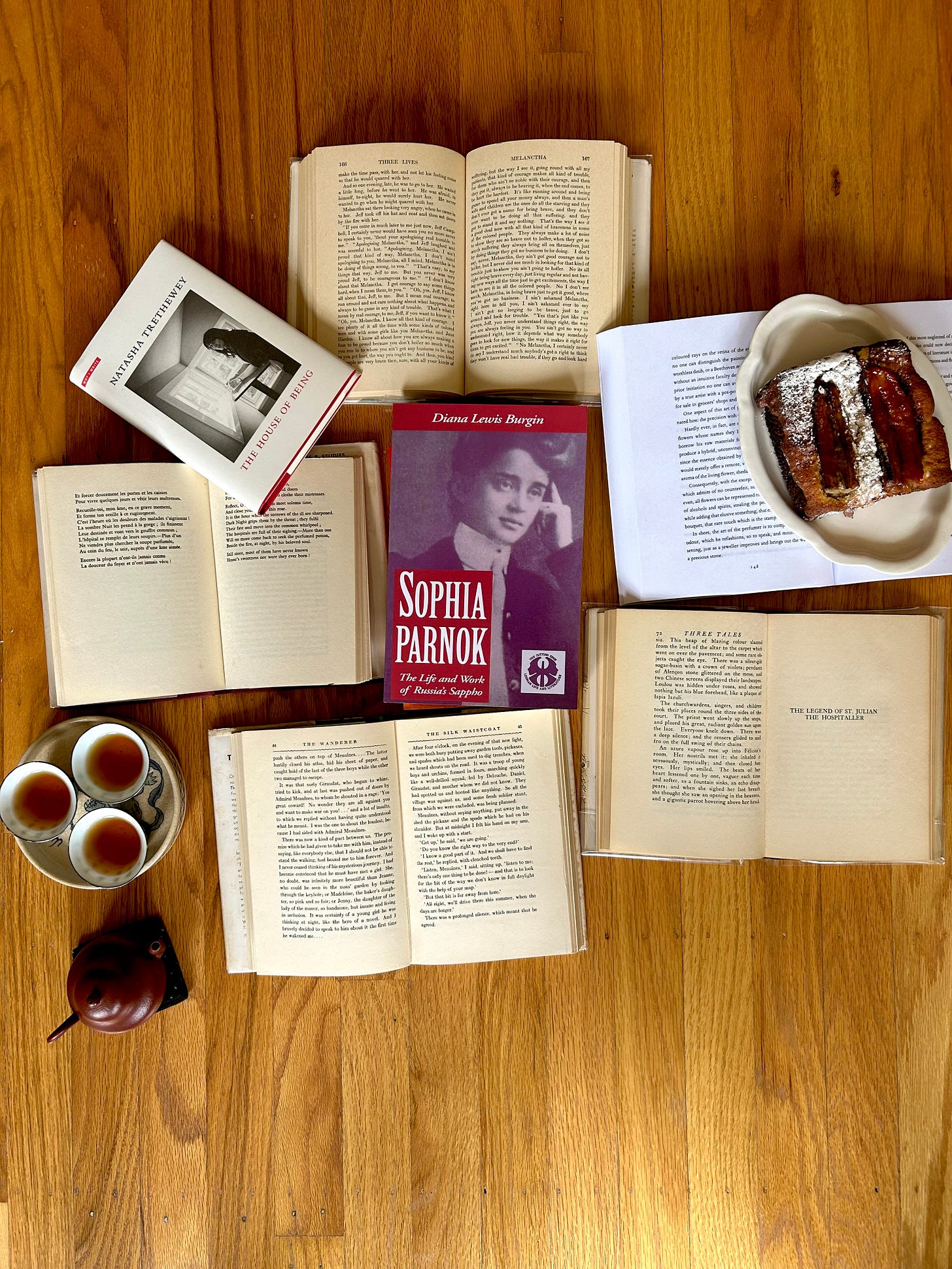

Diana Lewis Burgin's Sophia Parnok: The Life and Work of Russia's Sappho

Russia’s Sappho

My head is magnificently empty // my heart is dangerously full, wrote Marina Tsvetaeva, famous Russian poet, about her lover, Sophia Parnok, less famous Russia poet. Tsvetaeva wrote a cycle (series) of poets dedicated to Parnok, Parnok wrote poems back, a reader can trace their falling in love and falling out of it through these poems. Near the beginning of their affair, Tsvetaeva (characteristically) promised to steal an idol from an Orthodox church “that every night” that Parnok fell in love with said idol (she didn’t steal it). Tsvetaeva was shy about falling in love and lust with a woman. After she and Parnok broke up, Tsvetaeva later wrote that lesbians were inferior as they could not produce a child together, and motherhood was an essential longing for women.

Perhaps the latter was a barb toward Sophia Parnok. Parnok was infertile, and regretted her inability to have children. Unlike Tsvetaeva, Parnok was not ashamed of her lesbianism: she had her first affair with a girl at the age of sixteen, and continued to fall in love with women throughout her adult life. She’s known as Russia’s Sappho because she openly included her seven woman lovers in her poetry.

Most of what we in the West know about Sophia Parnok is through Diana Lewis Burgin’s Sophia Parnok: The Life and Work of Russia's Sappho (1994). It’s more than a biography, as it includes passages of Parnok’s poetry with analysis, and reads as easily and excitingly as any künstlerroman (“artists' novel”). The biography has a rhythm and meter of its own, as its seven chapters capture seven eras of Parnok’s lives, echoing the seven lovers Parnok wrote of.

Her Biography

Parnok’s writing supposedly had three qualities that set it apart from her contemporaries: her lesbianism, that she suffered because Grave’s disease, and her Jewishness. Add to that a certain wildness, a sort of emotional freedom and openness and a sense of tragedy that is rare in measured poetry. She was born to a middle class family in Pale of Settlement Russia, her mother died young, her father remarried, she felt unloved as a child and teen. Burgin wrote that Parnok had material wealth through her father in her formative years, and chose poverty and to be surrounded by love in her adult years. Parnok’s desperation to escape her father was so great that she married a man, a relationship that was enjoyable at first but quickly fell apart. Parnok feared that her writing lacked skill and talent when she was young, brought on in part by that writer’s feeling of being unable to fully capture the wonderful spirit of the way the thoughts read while in one’s head and before they were transferred to the inferior page. Through mentorship and support, Parnok eventually published her first book of poems so as to gain financial independence from her father. Parnok also wrote opera librettos, which were about her affairs and loves. She also found a different type of mentorship in an older Russian woman, who helped her with an early paid writing gig.

In Moscow, Parnok had a stable love that she left for a passionate, stormy one with the passionate Marina Tsvetaeva. Their peers commented on how the two women were physically obvious at events, making their same-sex affair obvious. It ended when Parnok met Lyudmila Vladimirovna Erarskaya. Erarskaya was Parnok’s longest love, through the Russian Civil War (revolution of 1917). Her lover contracted consumption (tuberculosis) and after their relationship ended, Parnok was bedridden because of stress and Grave’s disease. She still wrote until her death, at the age of forty-eight.

On Bravery and Censorship

To be openly lesbian in 1890s - 1930s Russia was brave beyond what most of us are capable of. During this time, Anton Chekhov wrote (in a letter): “The weather in Moscow is good, there's no cholera, there's also no lesbian love...Brrr! Remembering those persons of whom you write me makes me nauseous as if I'd eaten a rotten sardine. Moscow doesn't have them--and that's marvellous.” Burin also mentions male mentors of Parnok’s who were fascinated but equally uncomfortable with her lesbianism. To write openly about loving women, especially when your mentors and the literary establishment, to say nothing of normal, less creative society, don’t approve of lesbianism is astonishingly brave.

That Parnok was writing openly while also writing for money was more brave. Other lesbians of her era, say Natalie Barney or Romaine Brooks, could defy societal standards because they were independently wealthy, they had no need to sell their work and they could live above the rules, as the wealthy do to this day. Parnok had no such privilege. She dreaded becoming dependent on her family, which would mean a loss of love and freedom. That she made a living, however poor, doing so, writing in newspapers and translating French while continuing to write and publish the poetry is admirable. It speaks to her talent and her flexibility of spirit, one we would do well to emulate today.

Through most of USSR period (post 1917 or so), Parnok’s work was unavailable because of censorship. Parnok tried to modify her work during that era to save it from the censors, she was that desperate to work and publish. It was a wise choice, one made by other queer writers such as Virginia Woolf; compare the ease of publication of Orlando to the censorship trials of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. Parnok’s work wound up censored later, unavailable in the USSR for decades after her death. It wasn’t until 1979 that it was available, and even then, it was first published in the US by a Soviet scholar.

Today, lesbian/queer Russian writers such as Oksana Vasyakina keep the spirit of Parnok alive. They write under the more explicit threat of criminalization for “propaganda” for writing about LGBTQI+ experiences. Vasyakina’s single work translated in English (review linked) is more honest about self than any work I’ve read. In Wound, Vasyakina lays bear her hellscape of a childhood, personal flaws, and mental illnesses. Parnok could be seen as a forerunner of Russian queer literature, her far-ahead-of-its-time honesty about her lesbianism inspiring and helping create a tradition of courage in later Russian queer writers.

That bravery in queerness feels needed, especially in light of conservative movements to silence across the world. For writers such as Parnok and Vasyakina to continue to write under the threat of censorship and worse, to refuse to stay silent, is an inspiration to the rest of us who have lived under greater freedoms that might now be threatened.

A Poem

Here is one of her poems. This is a translation from Diana Lewis Burgin’s website, there’s another translation on RuVerses.

91.

Not spirit yet, but barely flesh,

I have so little need of bread,

That if I were to prick my finger,

I’d see a drop of sky, not blood!

Yet there are times: I’ll pour a glass

Brimful of wine – but it’s unfilled,

And bread that I have salted white

Still tastes unsalted to my lips.

And whispers in my sultry dreams

Predict I’ll suffer from my body

Still more recurrent oddities

As if it was a pregnant wife.

Oh dark, dark, dark path,

Why are you so dark and long?

Oh curtain that had hardly opened

Only to be pulled and drawn!

To bear oneself to God, but then

Sink back in darkness like a stone,

And wait until a lazy fire

Shall burn right through you to the bone.

Thank you for sharing Sophia Parnok’s story—I had never heard of her before, despite being Russian. It’s incredible to learn about her courage and poetry, and I’m grateful for the chance to discover her work.

I did not know her at all. You are doing a great service to lesbian Herstory. Are you doing a collection of of these and reviews for Sinister Wisdom? Get Julie to do a talk with you and contact the Stonewall in Ft. Lauderdale they have a lesbian group that would love what you are doing.