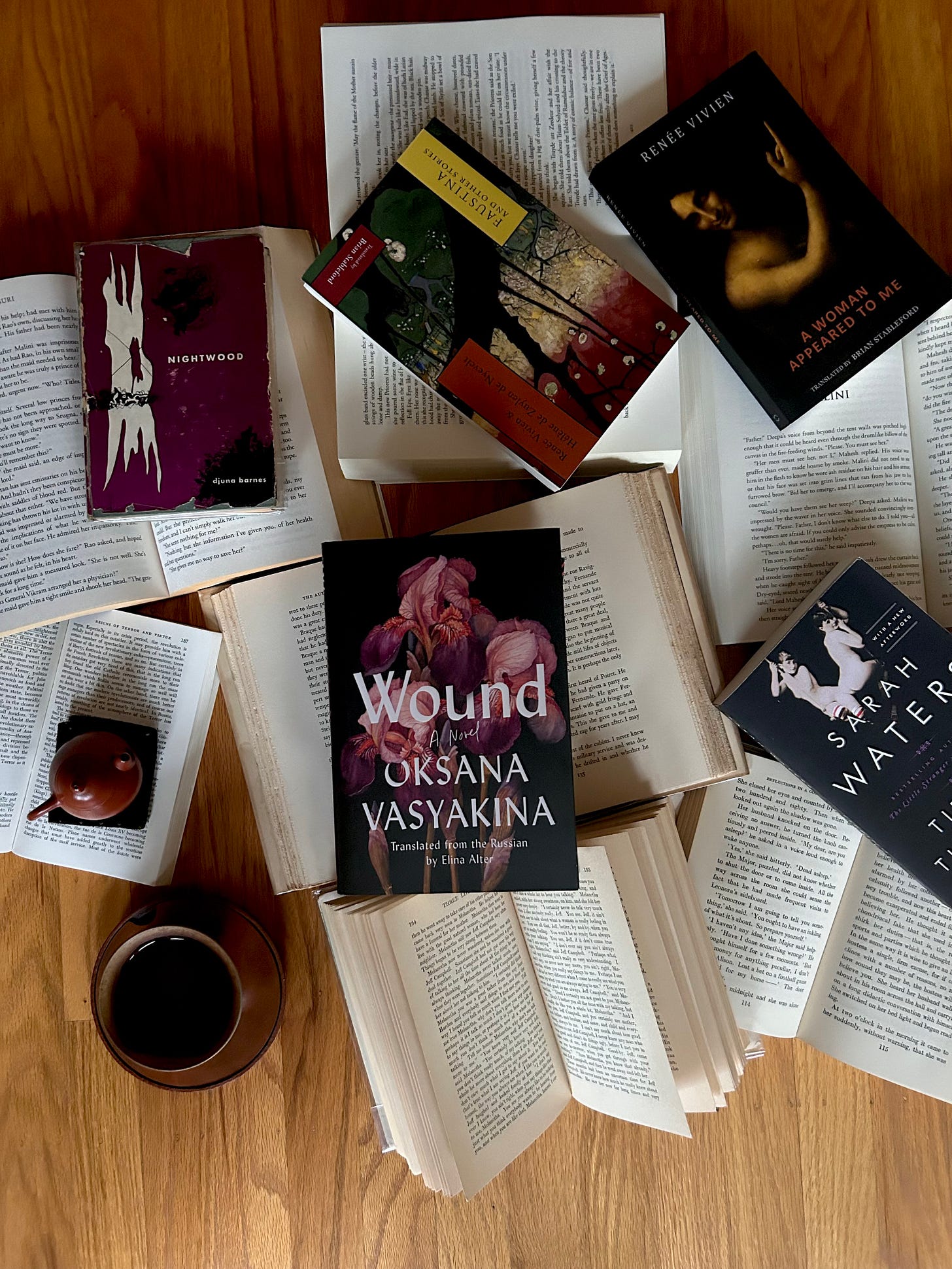

I read ‘Wound’, a translated work of contemplative autofiction by Oksana Vasyakina a few months ago. It’s unlike anything I’ve read before. It’s part travel narrative, following the author’s reflections on her childhood, her sexual awakening (as a lesbian), finding love, and especially, her relationship with the mother whose ashes she’s carrying on the journey from Moscow to Siberia. She writes: “The wound is there not because she didn’t survive, but because she existed at all.” Vasyakina’s relationship with her mother was fraught: her mother had a series of abusive boyfriends, and did not protect child Vasyakina from them. Her mother passed from breast cancer, and Vasyakina reflects on the symbolism of breasts, motherhood, and her femininity versus her mother’s attractive, conventional femininity throughout. One of the more striking observation in the novel is the pressure to conform to different standards in the lesbian community. Finding the community after struggling with same-sex…

© 2025 𝙅𝙤 ⚢📖🏳️🌈

Substack is the home for great culture