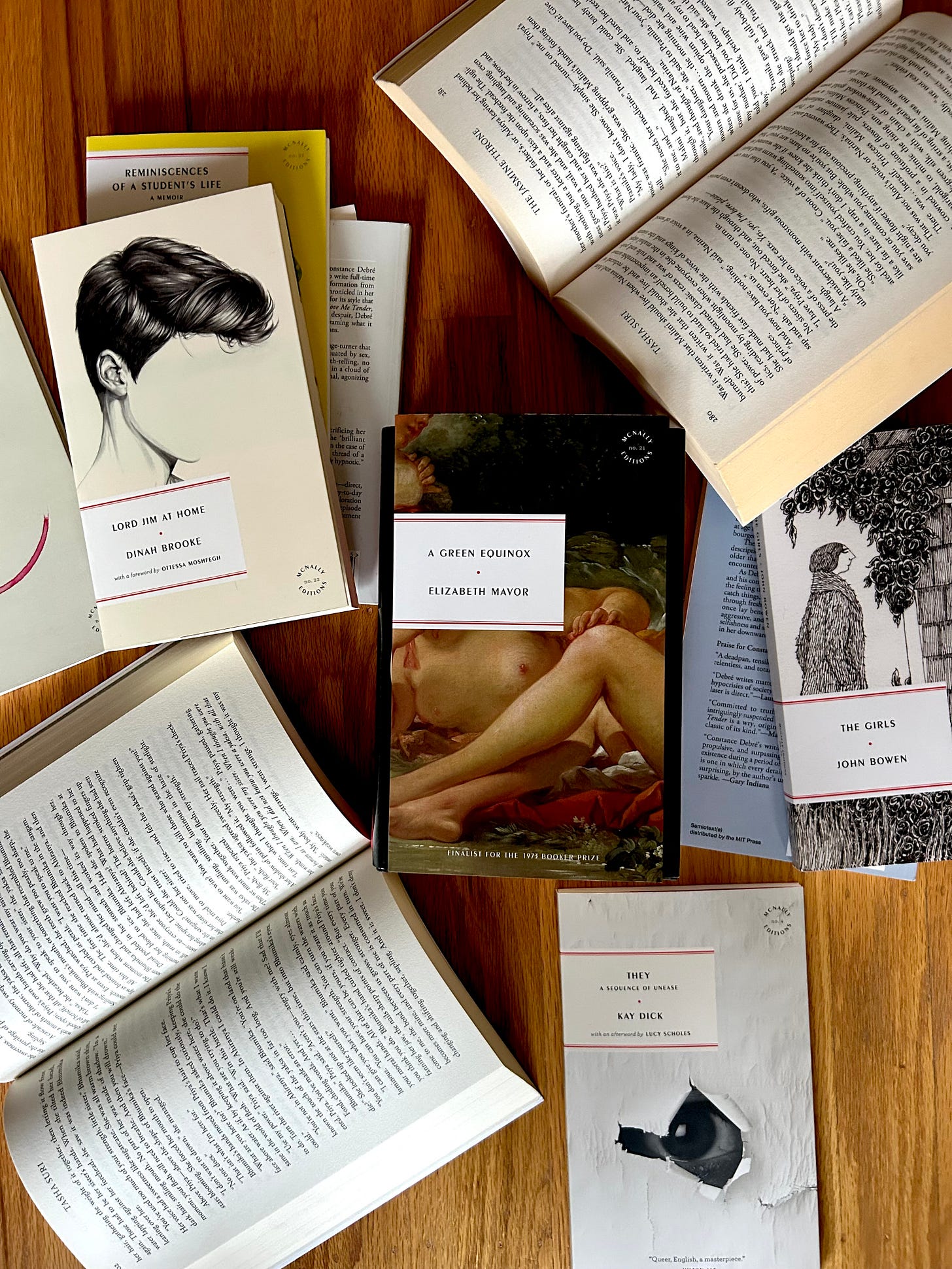

First, if you want to read Elizabeth Mavor’s A Green Equinox (1973), do not read the blurb. It gives away the entire plot of the book. As do most reviews (not mine here though!).

This book is not bad or anything, it’s just…meh. It’s a reflection on a certain British class, witty, sharp, satirical observations that gently poke fun rather than eviscerate. The heroine, named Hero Kinoull, is also sharp and witty and very much in line for unwed, smart heroines of the midcentury, a bit like Lynn in In Thrall grown up, the sort of spunky heroine who’d make great conversation at dinner if she felt you were intelligent enough for her to want to engage with you. “Friends have, of course, tried to persuade me that if such a passion is not a sickness then it’s a sin, like hubris or tristitia or worse of all accidie, that devilish torpor, that restless sadness, which of all them perhaps most nearly resembles what I suffer from, and they have advised me to stop squandering my vivacity and intellig…