Jane DeLynn’s In Thrall (1982) is the story of a lesbian coming-of-age and coming to terms with her homosexuality. The heroine, Lynn, is the teenage version of the child heroine is reminiscent of Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy (1964) and E.L. Konigsburg’s From the Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler (1967). Lynn is a little older, sixteen, but also a precocious New York prep-schooler. She frustrated by the Jewish middle-class conformity of her parents, who she calls “despots”. Like Harriet, she internally mocks those around her, including her girlfriends, her maiden antique-loving aunt, and the boyfriend she keeps around to fit in, 1960s style. As with other books, you have the sense of reading something of its time, of a snapshot of a culture that’s shifted and faded.

You’re already sensing something is different when Lynn opens by telling you that she always has crushes on her teachers, and her current crush is her English teacher, Miss Maxwell. She’s becoming aware of what the crushes on female teachers signals, and she’s deathly afraid that it means she’s not normal. To her limited knowledge, lesbians are gym-teacher types, with mustaches and crew cuts, and blue-eyed Lynn wants fit in and be “MC” (a subtle reference to middle class and respectability). So she puts up with the awkward, undesired fumbling of her boyfriend, and competes for unwanted male attention with her girlfriends. She challenges her parents, and wonders why her mother cries every night. Lynn’s intelligence is a shield, and her swagger is a sort of defensiveness, she makes her judgements offensively so as to leave little room for others to question her. She’s contradictory: she wants to be exceptional and above the fray, but she also wants to conform and be beloved by the fray she looks down on. Despite her teenage angst, or maybe because of it, you fall a bit in love with her, maybe see yourself in her bravado, and even if you don’t, you want the best for her despite her pretensions and her misanthropy.

Miss Maxwell, her thirty-seven year old teacher she’s crushing on, sees right through Lynn. She invites her over for tea. Unlike everyone else around her, Miss Maxwell is Lynn’s intellectual equal, returning her brattiness with gentle insults that make Lynn question herself, answering Lynn’s intellectual postering with her own. She questions Lynn’s typically teenage dislike of her parents, calls out her immaturity. Her directness is refreshing to Lynn; rather than pretending Lynn will get into Radcliffe, Miss Maxwell tells her that her no teacher will give her the sort of reference she’ll need for her dream college to accept her. Their courtship is combative, and the combativeness draws them in, deepens the fascination. So yes, it’s described as a love affair. And yes, it’s also definitely statutory rape that built off of grooming - of both building up a teenager’s confidence then making her question it before shattering it, and of exploitation of that child’s loneliness - the loneliness of the outcast and the misunderstood, of a child that is vulnerable because no one else is willing to accommodate or accept her burgeoning lesbianism. It’s insular and the emotions are fever-pitch: Lynn obsessives researches and questions her options as a homosexual and declares her eternal undying love, while Miss Maxwell has risked her reputation, her job, her pension, and threatens to end her life if their affair became public. We never learn much else about Miss Maxwell beyond a minimal biography, not even her first name.

The physical part of the relationship begins after Lynn writes a letter declaring her love. Lynn is in equal parts excited about the possibility, and dreads and fears it. Her first kiss lifts her off the ground and into an enchantment that she can’t stop. Her use of the word enchantment tells you so much about the relationship. Thankfully, those parts are only hinted at as the narration cuts away just as the two begin to remove their clothing and climb into bed. Lynn isn’t the first student with whom Miss Maxwell has abused, and Miss Maxwell knows Lynn will probably end their affair she grows up. Near the end, Lynn pokes fun at her teacher’s mustache, and her feelings of shame about her “overweight middle aged” lover kissing her in public are signs that Lynn’s enchantment is wearing off. After Lynn gets accepted into college and through a snowballing series of events, this sad affair will draw to a terse but calm close.

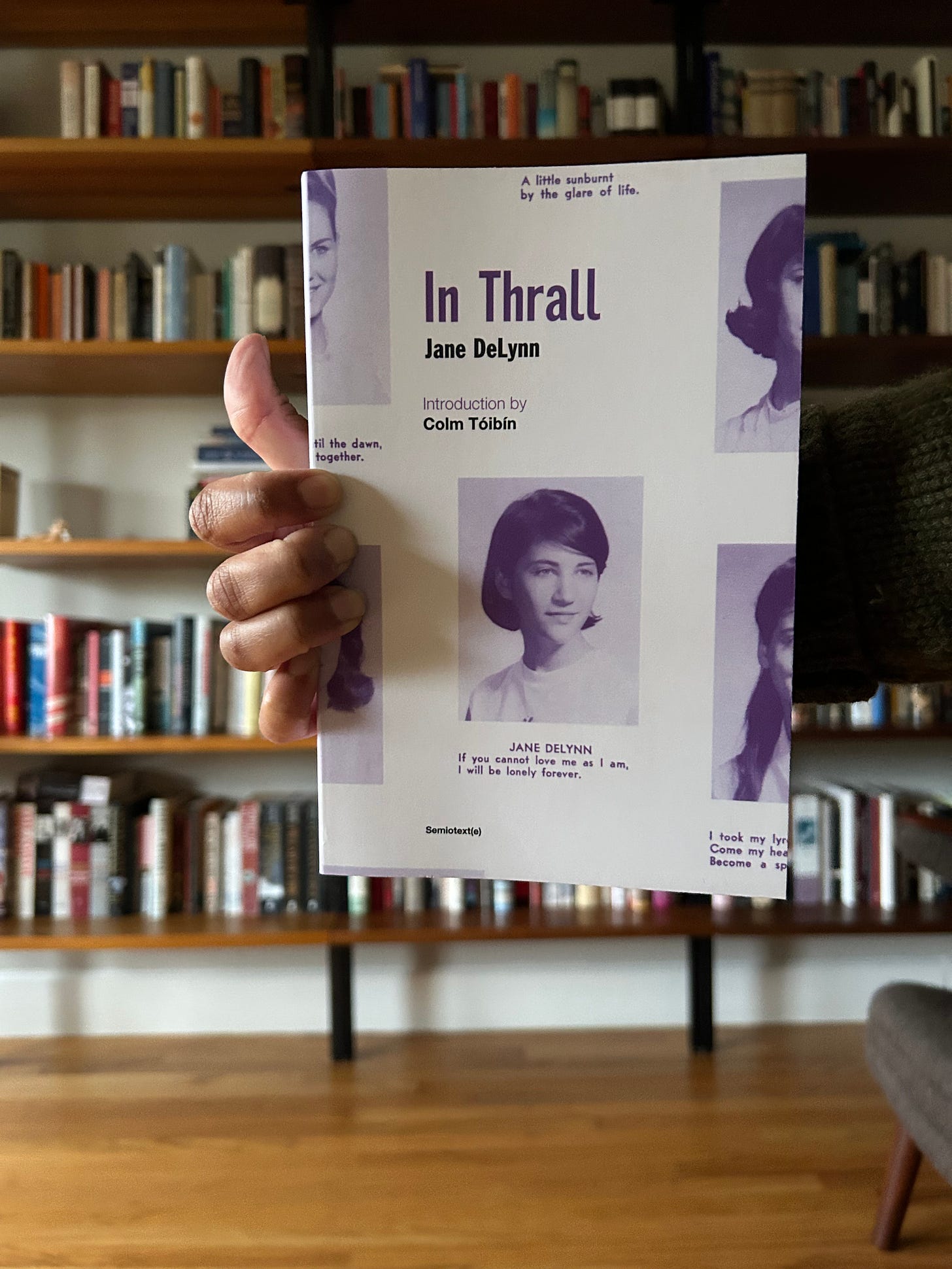

This story is presented as coming of age, but it’s unknown if Lynn has come into her own. There’s no hint of what will become of a grown up Lynn, no tidy ending, nothing that has the feel of a cinematic soft-glow ending with an adult narrator looking back at this period of her life. Much of lesbian literature becomes overly focused on morality, a forced ending that can be categorized as “happy” or “sad”. In avoiding that, DeLynn’s ending is true to life, just as her description of the exploitative affair and abuse is delicate and balanced. It’s a great book, and I’m glad it’s in print again as it was re-released last week by Semiotext(e).

My next review will be of Han Suyin’s Winter Love (1962)…which briefly handles damaging affair between a teenager and her manipulative teacher very differently.