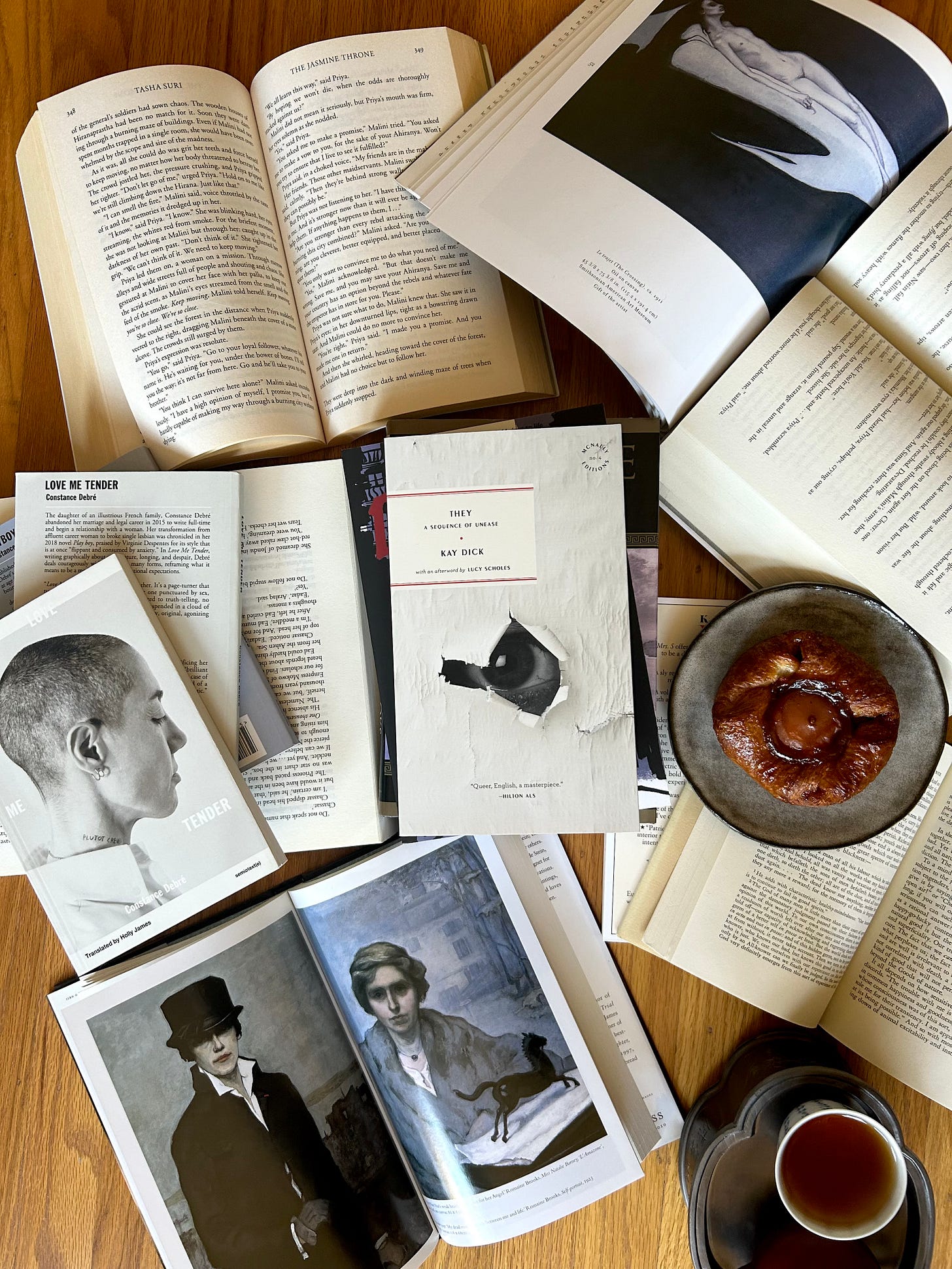

Kay Dick’s They (1977) was out of print until McNally Editions reissued it. What’s surprising about this is that K.Dick was the first woman director at a respected publishing house at the age of 26, worked as a reporter, and wrote several novels, and this one won an award (the South East Arts literature prize). She also lived with a female partner for twenty-two years. Surprising also because as well as those markers of prestige, she’s an excellent author, and this is a speculative, dystopian novel, the sort of novel that has all the signs of being beloved through the ages. An old copy was rediscovered by a literary agent in a charity (thrift) shop in 2020, and now it can be loved again.

For a dystopian novel, it’s quite beautiful and cozy. K. Dick’s prose is beautifully modernist, a masterclass in creating unease, and how to tell a story without an excess of description or word. There’s a narrator, whose name and gender are never revealed. Characters enter and exit. It begins with a …