The true first feminist speculative fiction author

On the West's ignoring feminism in the East.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915) is usually called the first utopia feminist author here in the West. If you search-engine “first feminist speculative fiction”, the answer you’re give is…Clare Winger Harris’ The Fate of Poseidonia (1927), which Wikipedia also calls the first feminist science fiction.

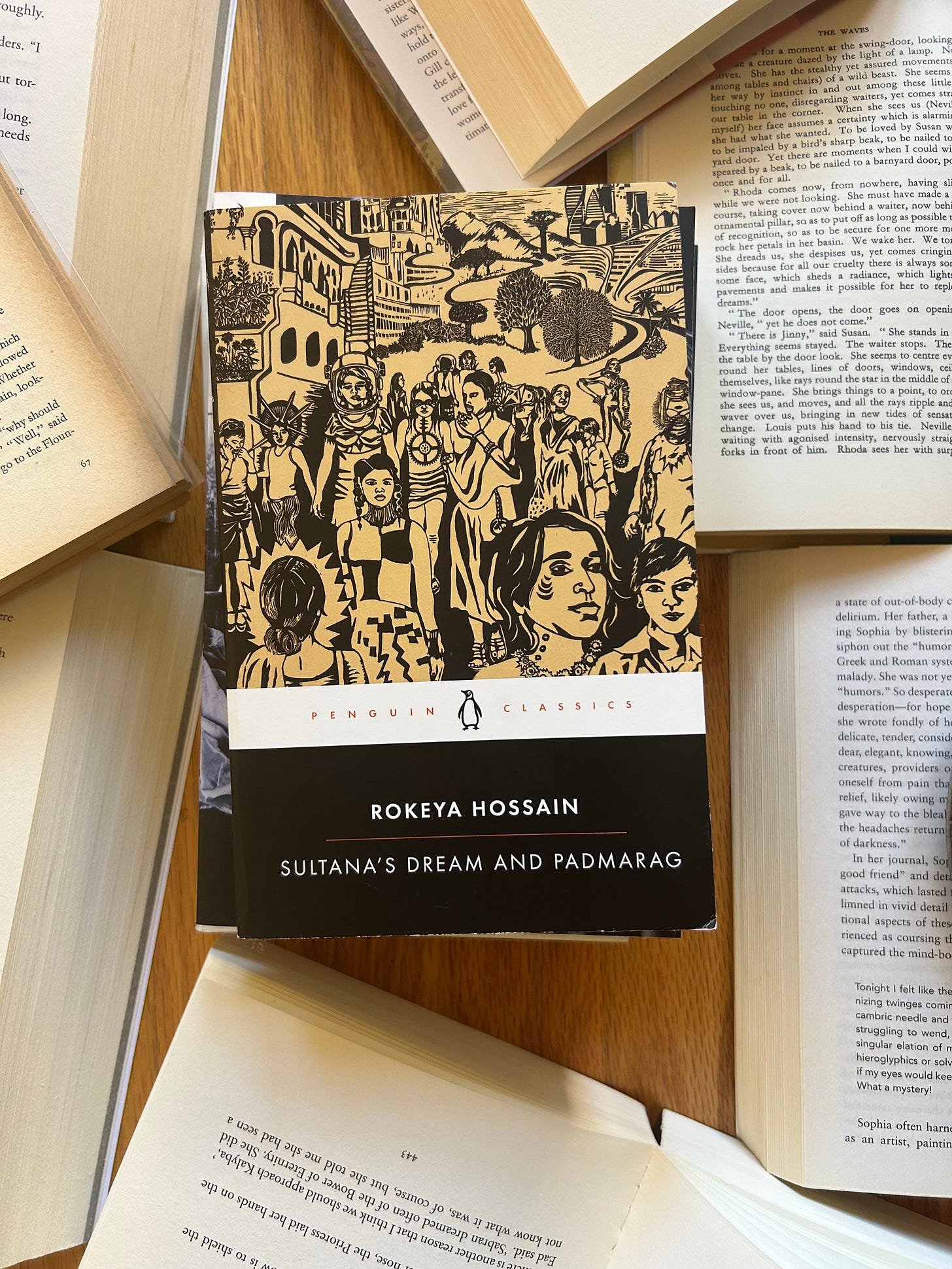

They are both pre-dated by Indian-Bangladeshi author Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s Sultana’s Dream (1905), which she followed up with Padmarag (1924). The reason that Hossain’s work is forgotten in the West is self-evident: she’s not Western. Yet, Hossain is and was an enormously successful author. In Bangladesh, she’s revered: December 9 is “Rokeya Day”, and she’s had a stamp issued in her likeness. In her lifetime, she advocated for equality of women, fighting so that women would be seen as rational beings as men are. She advocated for the end of the gendered division of labor. She believed education to be central to women’s liberation, to that end, she knocked on doors to persuade citizens to send their daughters to school. She founded the Muslim Women’s Association in 1916, and presided over the Bengal Women's Education Conference in 1926.

What’s lasted and influenced generations of feminists and women’s liberations in Bangladesh are her stories and novels. Sultana’s Dream is about a literal dream of a woman who finds a magical land in which women are rulers and work outside the home, and men are kept in purdah, that is, sequestered away from society, kept out of jobs and education, for their own well-being and safety. In this world, there is no violence, nor any lust for acquisition of more than one comfortably needs nor any colonist, expansionist drive.

Padmarag is a novella focused around a sort of women’s center, Tarini Bhavan, that educates, shelters, and empowers women. The head of this center, the CEO or executive director of sorts, is a woman, and her administers and the leadership of the center are all women. The women received food and shelter in exchange for their services. It’s a powerful story, with many smaller tales of individual feminine oppression, as women of all races, religions, and national origins suffer. There’s a Western women who has escaped an England that will not allow her to divorce a cheating, mentally troubled husband. There are Hindu and Muslim women escaping cruel in-laws and abusive husbands. In the end, the central character of the story choose to remain in the woman-centered world over a marriage that would have brought her greater financial wealth and glamour.

There are several ideas that tie both tales. In neither story does Hossain mention communism or socialism, yet she repeatedly expounds that the women in this women-led worlds are provided “each according to [her] needs”. There’s the idea of a sisterhood, a sort of competitive women-led world in which women exclusivity help one another and hold one another in the highest goodwill, which seems a fiction onto itself and is the greatest weakness in her work. The characters in both are thinly drawn, as are the plots, and the characters are more symbols with stories to tell than real people. Hossain tells both stories delicately and playfulness so that they never feel heavy or ponderous, and she draws upon humor, satire, and irony to rely her message.

It’s unsurprising that the West has ignored a highly respected feminist author, as her existence goes against the narrative that the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa are terribly backwards nations in which women are horrifically oppressed, whereas women in the West have achieved liberation. To that end, sati (bride-burning) and child marriage were used as justifications for the British colonization of India: the idea was that India had to be “liberated” by the West to free it of such practices. Yet, the British also forced upon India one of the world’s first anti-homosexual laws: code 377, as the British were horrified by Hinduism broad acceptance of homosexuality and of trans people. Today, polling data shows that more people in India accept trans folks than people in the United States, and yet, in my personal experience, most of my homosexual and trans friends presume the opposite, and presume that women and queers are horrifically oppressed and at extremely high risk of death for being out in comparison to the US. We also know that the West has a serious problem with child and forced marriage, and child marriage is an epidemic in the US, and that 8% fewer more Americans find gay and lesbian relationships morally unacceptable between 2022 and 2024. Today, Americans are horrified by Iran’s treatment of women, ignoring that the British and Americans deposed the democratically elected Iranian president - ending and setting back the possibility of democracy and the liberation of women in Iran and the Middle East for decades, and reinstituting what Hossain, over a hundred years ago, called the subversion of Islam as a means to oppress women. And we see that today with pinkwashing as a justification for the ongoing oppression of Palestine. One of the reasons the British gave for its conquest of the dying Ottoman Empire was to save white women from rape by non-white men. In its takeover, the British gained control of Palestine and the British Mandate began. Just as organizations in Palestine fight for LGBTI+ rights, Hossain is but one example that there are people in the East that also care and work towards women and LGBTQI+ liberation. And the examples I provided are but a few of the many, many examples of Western justification of oppression, when the West also has a ways to go in the liberation of all.

I recently taught Sultana’s Dream (virtually) to a university class in India and one of the students introduced this game based in the book to me: https://www.entersultanasreality.com/about.html. The students loved the story but had not read it before.

Rokeya Hossain is my author for Bangladesh! I've read Sultana's Dream and looking forward to Padmarag.