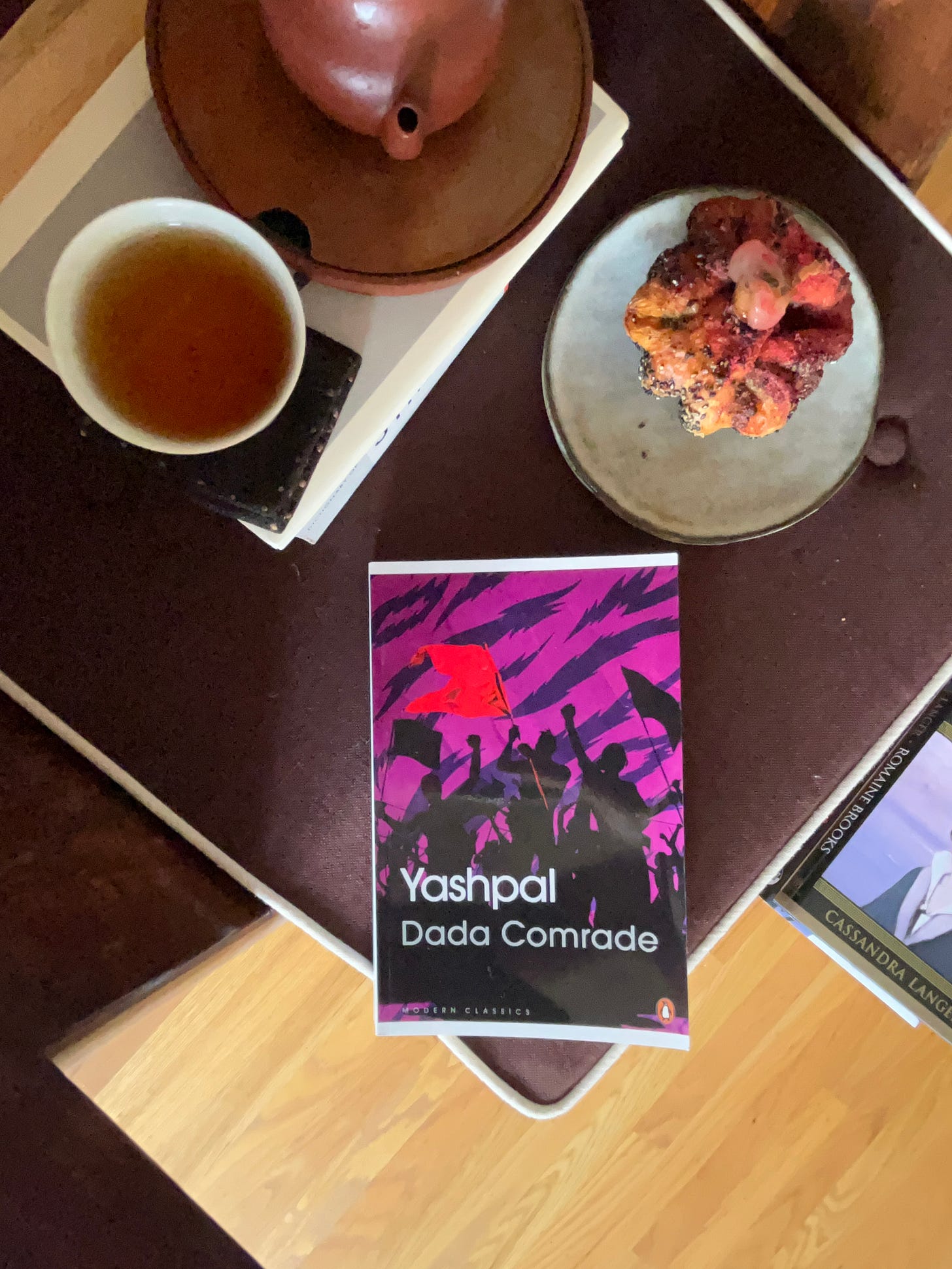

Yashpal’s Dada Comrade (1941) is essentially a morality play wrapped up in a novel that’s also Yashpal’s biography. It’s Yashpal’s debut novel, and it’s an extremely sophisticated, thoughtful debut. It’s not autofiction, losing something of the feel of autofiction in Yashpal’s choice to write in the third person, and to alternate point-of-views between a few characters. The main characters are Harish, the stand-in for Yashpal, and his love interest, Shailbala (Shail). As is more typical of novels by South Asian authors than Western ones, there’s an enormous cast of revolving characters that are interlinked. While Yashpal’s a brilliant author, I cannot see him growing in popularity in the West, because unless the reader had deep insight into Indian culture, the reader would be lost. A basic understanding of India’s fight for freedom against British colonialism would be helpful also, but it’s not necessary to understand the novel.

The freedom fighters and their dynamics are the crux of the novel, and the dynamics and philosophies Yashpal brings up throughout are still relevant and applicable to other revolutionary groups and conflicts. Yashpal was a freedom fighter that had joined a political party that had some Marxist leanings, one that eventually wanted to assassinate him. He writes about this experience through Harish’s experience, and tells you the central theme of his novel in his foreword “when, as a consequence of the growing age of human society, the swaddling cloth of its infancy starts oppressing its body, would it not be better at the time to create for it an extensive cloth of new ideas? Must we constrain its body such that it fits within its old limits? That is the question Dada Comrade invites you to consider.” The Dada (for most North Indians, dada means “grandfather”, but Yashpal uses it to mean “older brother”; in my family, we used to it to mean “father’s older brother”…the concept of wise older male remains consistent), and the dada of this novel is a petty, power-hungry party leader believes that Harish and Shail’s advocacy of modernism and new approaches are a personal affront to him. He has the cult-like leadership and following that’s still true in radical groups today, and as with radical groups today, that cult-like following and lack of original thinking are crippling to the deeper purpose of the group. Yashpal uses conversations between characters to espouse his philosophies. As with Jhoota Sach, he advocates against the traditionalism of Gandhi in Dada Comrade.

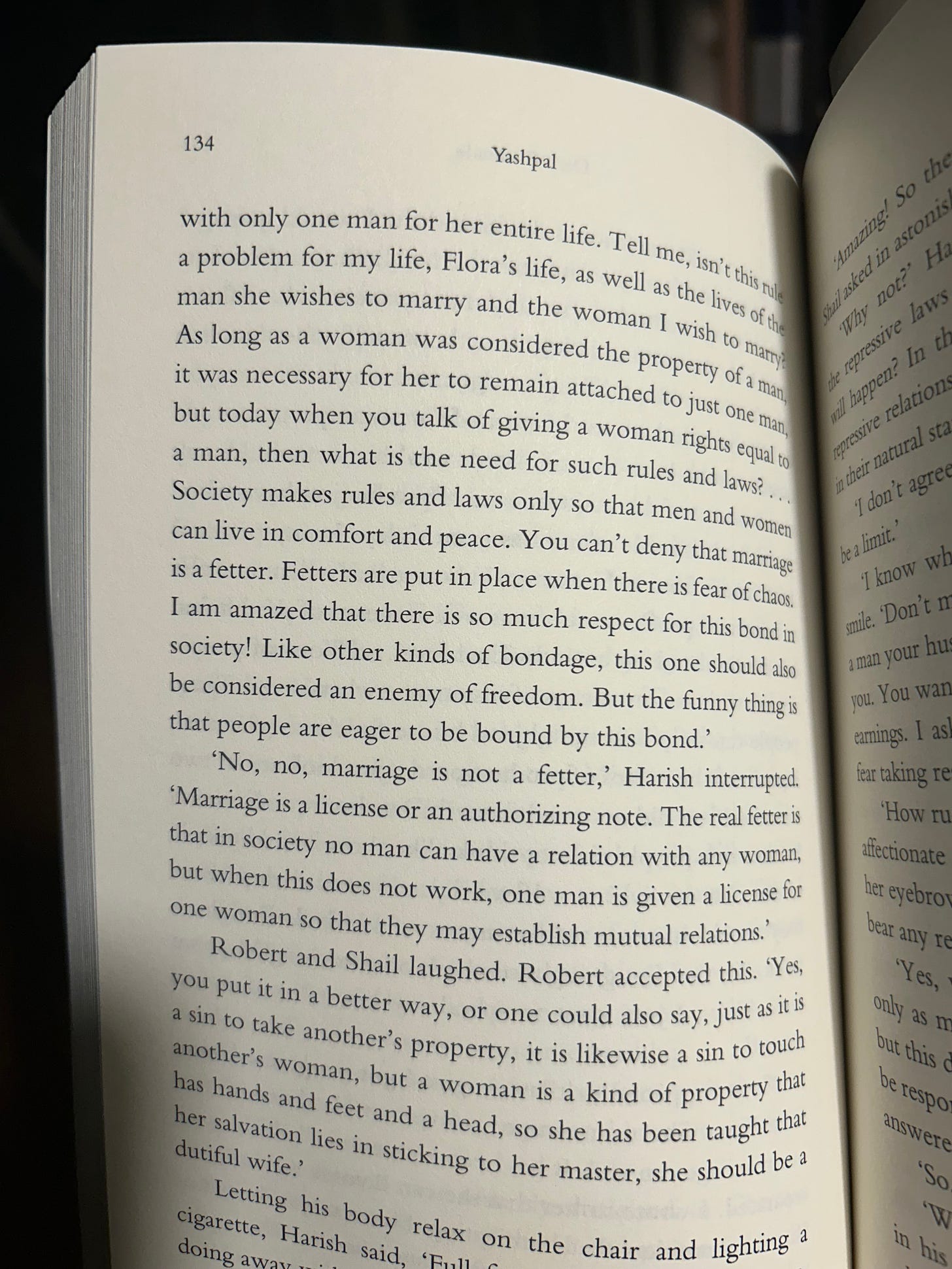

Like Ernaux, Yashpal advocates for women to have an equal ability to pursue sexual pleasure. In Happening (2000), Ernaux writes that she felt like man in pursuing pleasure, and hadn’t conceptualize the difference between herself and the men with whom she pursued that pleasure until her unwanted pregnancy. Yashpal advocates for access to abortion pills (in a book published in 1941) and contraceptives. Through Shail, he illustrates that the pursuit of sex is almost an inherent good, and it’s the repressed bourgeois that cannot look beyond morality that’s accepted without further thought that’s more problematic. Another woman, Yashoda, is the young wife that becomes radicalized through an event and through literature, essentially, she’s self-taught, and an encounter with Shail is the final push she needs to side with the freedom fighters. Yet, the characters of Shail and Yashoda are somewhat flat, they’re obviously symbols for Harish in their complete goodness and moral impeccability, whereas Harish grows and matures his philosophical leanings through the novel. This perceived weakness of this novel speaks to the weakness inherent in many revolutionaries: that while they advocate and fight for others to adapt values they claim to have, they often do not embody those values themselves and focus on pushing them onto others. However, the evidence shows that Yashpal isn’t of this type: he’s much more successful in espousing his feminist philosophies and in creating complex, nuanced female characters in Jhoota Sach (1960), showing his growth as a philosopher and as a writer.

Overall, the book is remarkable and was worth reading for me. If you have an understanding of Indian culture and history, I’d highly recommend reading Yashpal: he may not be the most well-known Indian author, but his skill, personal knowledge and experiences as a freedom fighter, and depth of his philosophical thinking puts him there with the best of them. His Jhoota Sach is considered by many one of the best accounts of Partition, an event generally unknown in the US, but one that resulted in the deaths of somewhere between 1MM to 3MM South Asians over a period of three weeks, and the vagueness of the number speaks to the lack of importance attributed to lives lost.