“I thought to myself Junkie, Jew, or dyke, it’s all the same, they’re just different words for the same thing. When you’re like Robert or my father or me, you just have to choose one of the three and stick with it, the reality it represents is irrelevant. Deep down, being gay means nothing to me….There’s no substance to any of it. Nothing of importance. Nothing essential….we’re all doing really badly. That’s how it is, that’s how we were born. So we’re forced to try things to try and get better….Sometimes it works for a while. Sometimes it doesn’t. Either way you have to do something with the longing, the absence.”

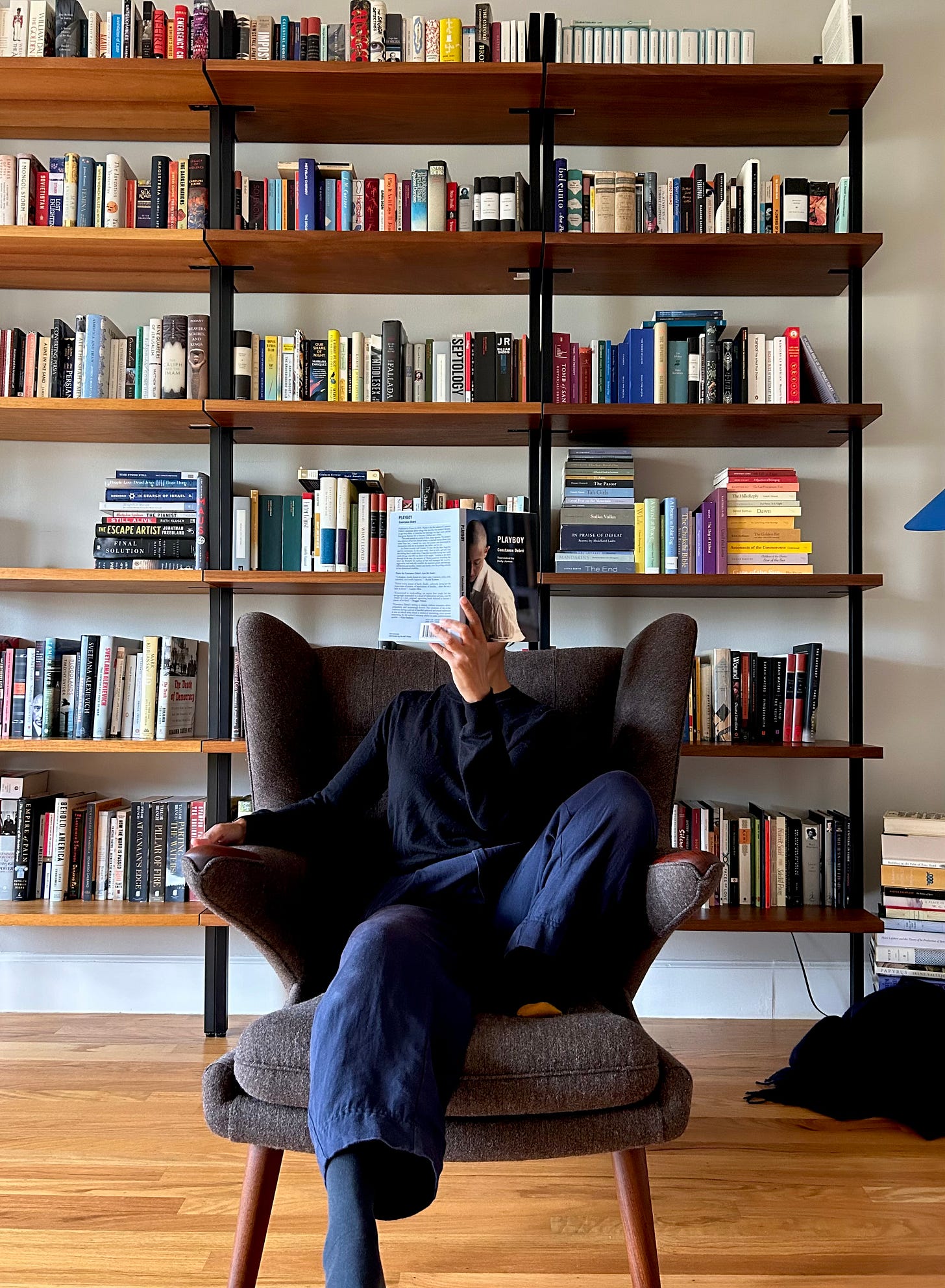

I sometimes wonder about that inner emptiness. It’s not something I’ve felt, I care too deeply about everything, in a way that more light-hearted folks must find exhausting. The above quote is from Constance Debré’s ‘Playboy’, and Debré’ would never claim to care too much or deeply as I would. She makes herself out to be nihilistic, and the world to be futile. She often spe…