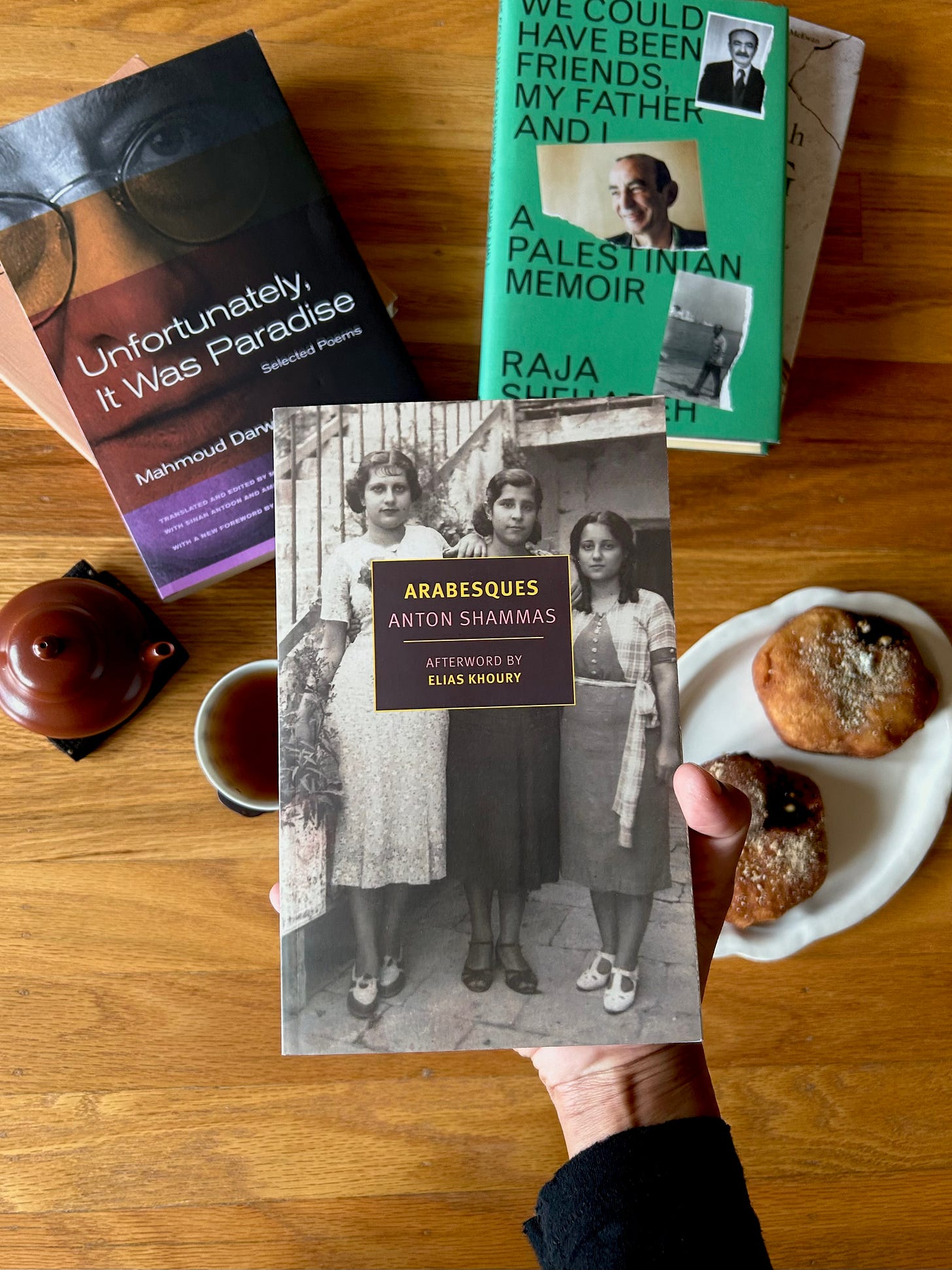

In Going Home (2019), Raja Shehadeh tells the reader about his life in Ramallah, Palestine, how he sees the city slowly changing during his walks, and that he is chronicling his love of his lifelong home because he believes it will not exist in perpetuity. In Arabesque (1988), Anton Shammas goes back to the beginning of the end: before Nakba to the 1936-1939 Arab rebellion against the British administration of the Mandatory Palestine, and the violence of 1948, which led to the expulsion of around 750,000 Palestinians from their homes, through the stories told to him by his family, colored by fatalist thought, surrealism, and magic realism (so common in stories past down through families in non-Western tradition), through to his time in Paris and his time at University of Iowa. He organizes Arabesque in two parts and shifts between the two, “The Tale” of the past, and “The Teller”, about his present. Whereas “The Tale” is warm, expansive, evoking Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Ismael Kadare, built off of an oral tradition that predates colonization and thus reaches past its influence, the latter part, “The Teller” is a lonely Palestinian Arab Israeli, cool, modernist, and regards constructing an identity as a person displaced and dispossessed of their ancestral home and associations, in short, a person whose thoughts have been colonized. It’s a sort of metafiction, questioning Arab intellectualism built off of knowledge and education acquired in the West. It’s also a sort of autofiction, yet not, as it is not linear nor does it follow a single narrative nor even a single identity; instead, it is a series of swirling, interlaced stories about his family and the people around them, going forward in time to reverse back, and a narrator split into three possible identities with varying futures. A plethora of symbols tie the narratives, often in red (red horse, red fields, the red hair of a Jewish woman versus the black hair of an Arab one) or olive-green (bookcase, olives, olive oil) but also olive oil or oil-slicked stairs, olive oil spilled that might have been used to tell of the future, and especially, through names (more than one person shares a name, a person might have more than one name) and identity. “I’ll write about the loneliness of the Palestinian Arab Israeli, which is the greatest loneliness of all.”

Unlike many simplified memes from Westerners on social media, Arabesque is not a flat postcolonial story of good Palestinians and bad Jewish settlers. Shammas shows its complexity: how it influences the culture and thought of the colonizer and the colonized, and how the entanglement of both parties cannot be simply undone (1). Here, an Arab wins a contract to quarry stone used to build modern Israel. Through this tale within a larger tale, he questions which claim to the land (the Israelis or the Palestinians) is older or more “correct”. He questions the Israeli Jewish identity and his ownPalestinian Arab Israeli identity, both are new, ancient, and shifting. “[T]he system of Arab education in Israel, at least in my time, produced tongueless people…without a cultural past and without a future. There is only a makeshift present and attenuated personality.” Shammas started writing Arabesque first in Arabic, then set that aside, and when he revisited and finalized the novel, he chose Hebrew, a language he called his “stepmother tongue”. This choice made Arabesque first Hebrew novel written by an Arab, but his work is widely read in Israel and this novel was praised there as well. Shammas believed (perhaps believes still?) in a sort of one-state solution, in which both Jewish Israelis and Palestinian Arabs coexist as equals. Shammas hasn’t written another novel since this one, perhaps because Israel has moved further away from that idea today, and Shammas himself lives in the US and is a professor at an American university.

I’ve intentionally left out details of plot of this novel, so that should you choose you to read, you’ll discover those slowly rather than knowing them immediately. I picked up this novel from a sale at New York Book Review, knew nothing about it when I did so, and I’m glad I read it without reading any blurbs, as it’s a more astonishing and enjoyable read if you read it that way. Should you choose to read it, I’d recommend reading Elias Khoury’s excellent afterword, and this essay by the Yale Review as follow ups. I also looked at Goodreads, and was surprised at the low score Arabeseque received there. Seemingly, many readers didn’t have much negative to say about the book, but critiqued how dense and difficult a read it was, or one popular reviewer repeatedly touched upon his astonishment about Christians and Catholics in the Arab world. Please disregard those reviews, as they speak more to the patience, learning, and lack of knowledge and comfort around reading about the non-Western world of the reviewers than they do of this book (2). If you have the patience to read it slowly and know that you may have to re-read pages, it’s a deeply complex, beautiful elegy to a world and worldview, like Raja Shehadeh’s Ramallah is fading into non-existence.

(1) I am also a person whose identity and family history has been directly impacted by colonization and enmeshment in the West. I see parallels between Shammas’ identity, the situation that affected his family, and the ongoing conflicts in that region, and my own; parallels that I hope allow me to have greater empathy and understanding of his situation and that of millions of people originally from that region.

(2) I clicked on a few of the profiles of the top reviewers, and they had histories of giving lower ratings to novels set in and about non-Western countries. I believe this is because the lack of knowledge of those cultures, traditions, and histories made those books more difficult reads, and the reviewers chose to lay blame on the authors rather than examining their own discomfort.