Derek Jarman was born in 1942 and in London. He was an vanishingly rare sort of artist: a jack of all art trades. In 1986, he won the Turner prize for a painting, and designed stages, wrote poetry, and designed costumes. Today, he’s remembered primarily for his experimental films, which also brought him monetary success. Tilda Swinton - who is mentioned many times by first name only in the book I reviewed here - got her start through Jarman. In a recent NYT interview, she mentioned his death as one of the first deaths that deeply affected her, the type where she learned what death was and what it means.

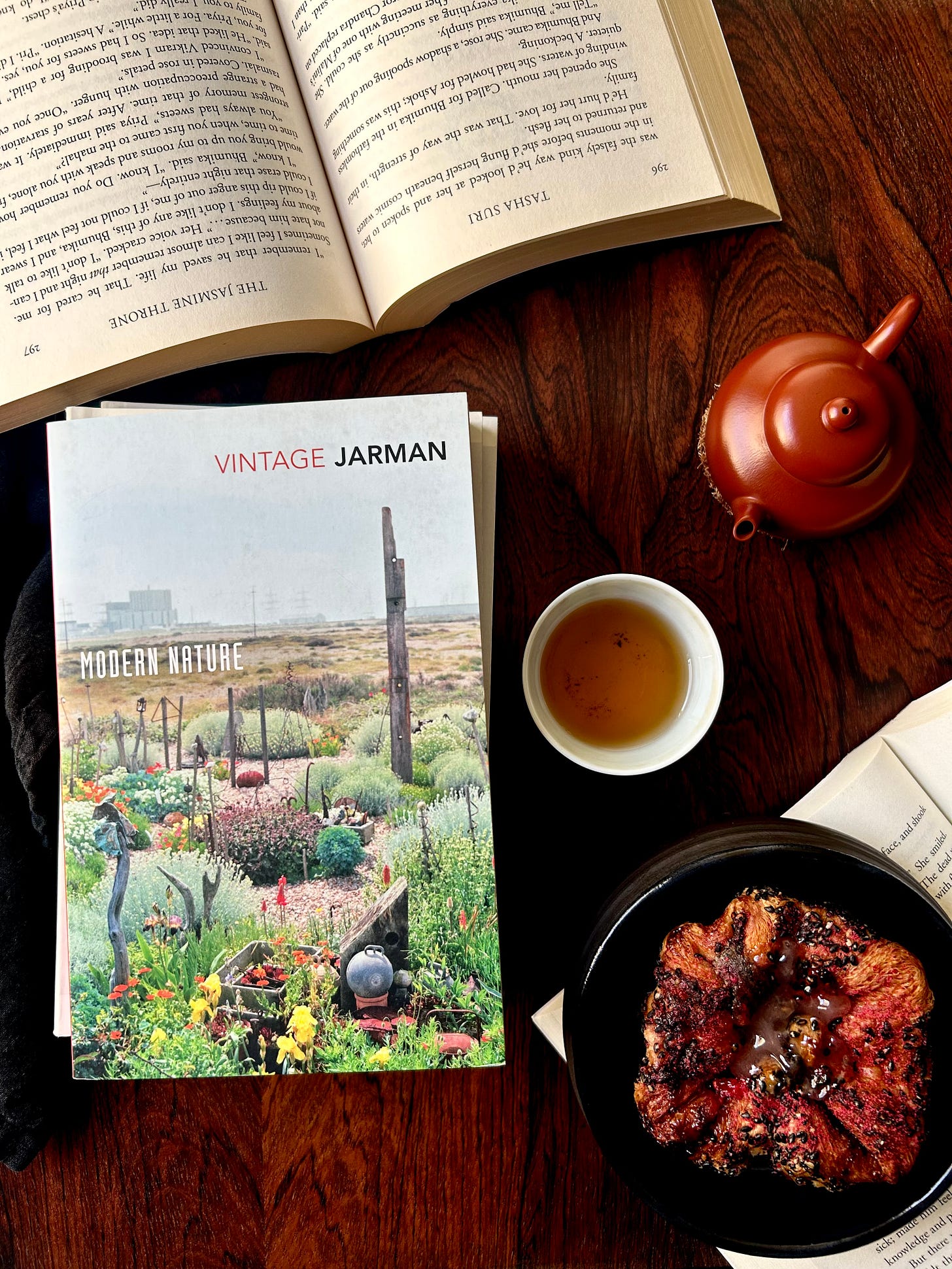

I write of Jarman in the past tense, he passed of AIDS-related complications in 1994. After he was diagnosed HIV-positive in 1986, he bought a cottage in a barren part of Dungeness (Kent, England) near a nuclear power plant, and turned it to a riot of color and texture, planting a garden that people from around the world visit today. Efforts to save the cottage raised £3.5m to save it from private sale, so anyone can visit today. His films, art, and garden live on, as does the book I review here, Modern Nature.

I first heard of Derek Jarman through that BBC article linked above, and immediately went and bought Modern Nature. It was during the early days of quarantine - the BBC article I linked was published within the first month of masking and quarantining. At that time, we were locked away from other people because our governments responded relatively quickly to pandemic (though perhaps inadequately) that had shown up a few months earlier.

Contrast that with the response to AIDS. In 1981, the first case of AIDS was recorded. It was crassly called “the gay cancer”. The CDC waited five years after the first case to release a campaign to spread awareness in 1986. The U.S. federal government funded an incentive in 1990. The NIH (Great Britain) developed a plan to coordinate research in 1993. In the meantime -

In the USA, by 1995, one gay man in nine had been diagnosed with AIDS, one in fifteen had died, and 10% of the 1,600,000 men aged 25-44 who identified as gay had died – a literal decimation of this cohort of gay men born 1951-1970.

Levine, Martin P., Nardi, Peter N. Gagnon, John H. Inchanging Times: Gay Men and Lesbians Encounter AIDS. 1997.

The implication here are clear, that “the gay cancer” mattered less because of the of population affected and dying, especially when compared to the modern response to COVID. In Modern Nature, Jarman’s sadness at his impeding doom is clear. Also clear are the sheer number of his friends and community affected, and dying also. Jarman does not brood, his personality and character aren’t of the negative nature: he also shows the strength of the gay community gathering to support one another.

Modern Nature feels like the opposite of the book I reviewed yesterday (Notes on a Crocodile) in that it’s a book about living even in the face of death. It’s a celebration of gay male community and life, even with faced with systemic neglect and death. As Jarman writes about his garden, he goes back to his birth and childhood, and questions his expensive education and the shame it instilled around bodies and sexuality. He writes about being a gay man in London during the swinging 60s, of finding gay spaces, and the thrill and constant fear of arrest as gay sex wasn’t legal and the police would arrest people for it (note 1), and a bit about the strange ways life changes once he finds success and a measure of fame. The life Jarman describes is enviable: he’s achieved the type of success he wanted, allowing him to create the type of art he wants while earning a living, he has a large circle of friends, he’s approached by young gay men (sometimes male sex workers) because of his art and fame, and he finds love with a computer scientist. After his diagnosis, he leaves London for the cottage. The garden he’s building is the first time he’s spent significant time in nature in the sense of gardening, and the title of his book comes from a friend calling a garden “modern nature”. Some of his plantings died in the salt air and chill winters, others thrive. Some of his friends, like Tilda, will have bright futures, and he lists off several who will not survive the epidemic, and a few that die during his lifetime. There’s the obvious symbolism of creating so much life while facing death, which Jarman handles without cliches, sentimentality, or banality.

I’ve read it twice, and I’d happily read it again for the gorgeousness of Jarman’s prose and the depth of his insights.

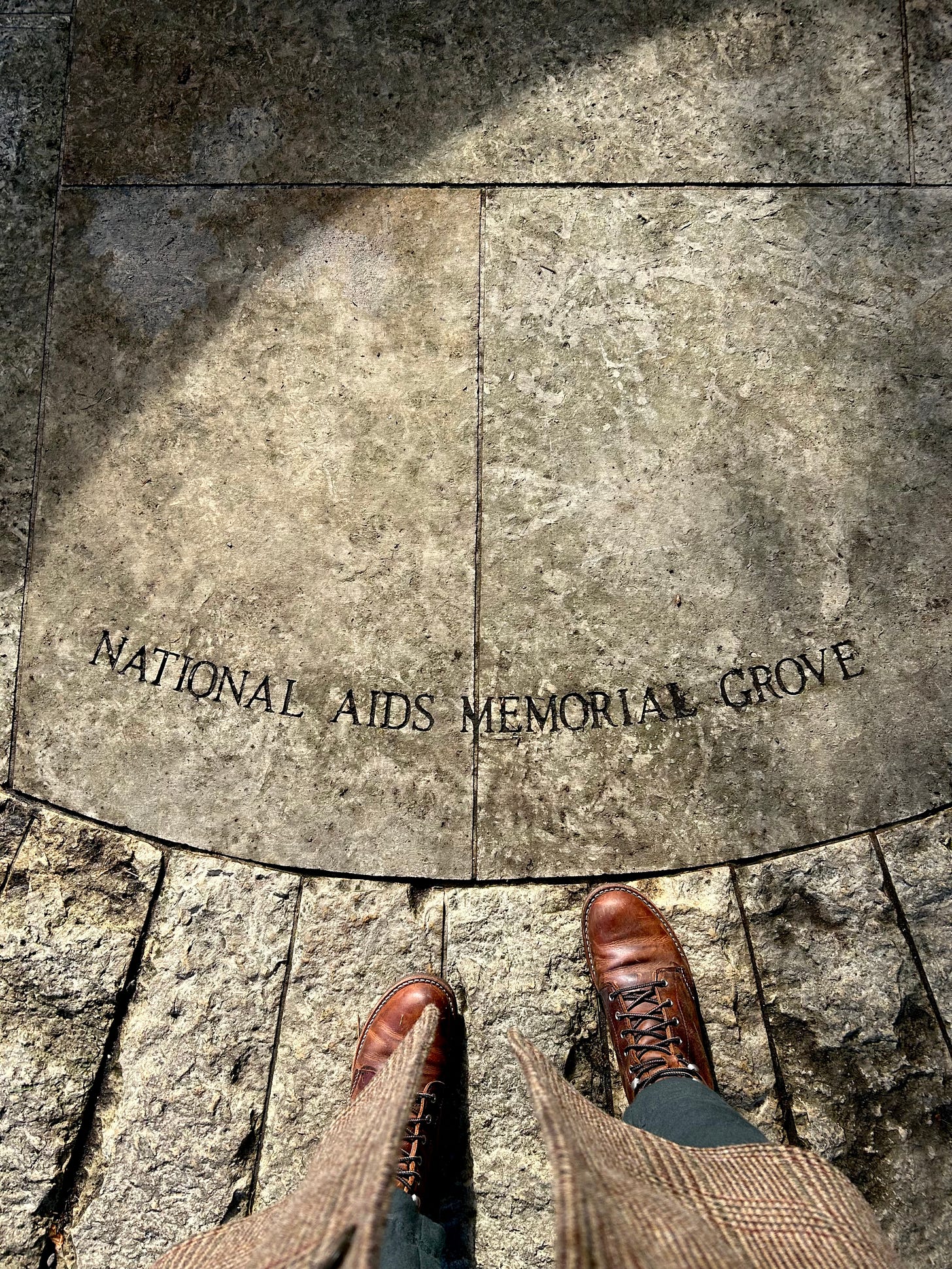

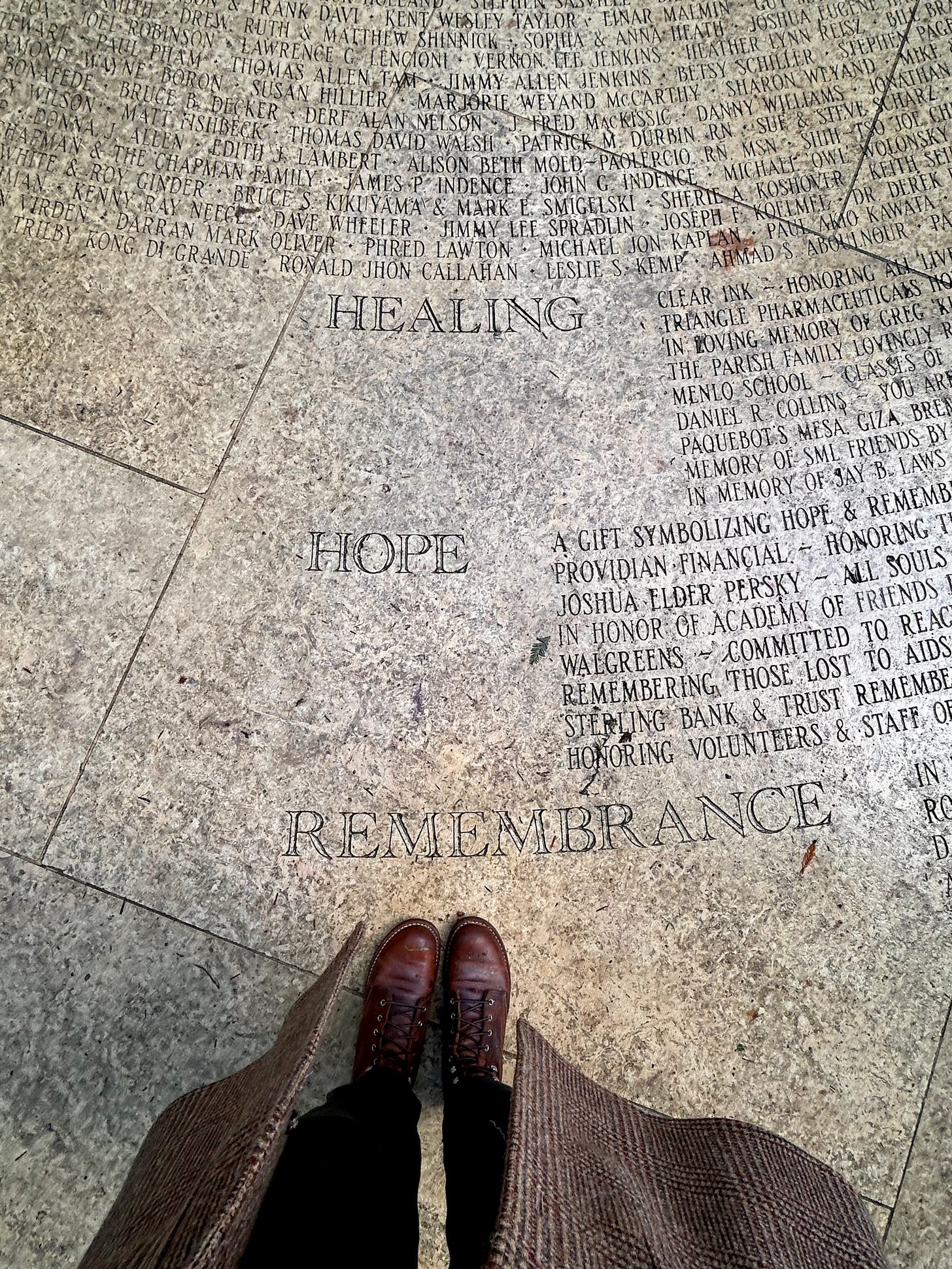

A bit of trivia: before the AIDS epidemic, the acronym used to be “GLBT”, and after it was changed to “LGBT..” because lesbians were willing to help (provide care to) gay men affected by the illness, in an area when transmission was misunderstood and people avoided HIV+ folks in fear. The latter two photos are of me wandering through the AIDS Memorial Grove, which is in San Francisco and is one of my favorite areas in Golden Gate Park.

This was great. Thanks for sharing.

This is just so sad but also so beautiful